Amos Tversky (left) and Daniel Kahnement (right)

Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in 2002 for the work he, and fellow psychologist Amos Tversky, began in 1974 when they and published their article “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” in the esteemed academic journal Science (Vol 185. Pp. 1124-1131). Tversky and Kahneman sought to understand how humans made decisions in uncertain situations. This work suggests people use a series of mental processes to make decisions and the underlying machinery of these mental processes tends to make predictable errors. Their findings have profound implications for our understanding of mental health.

Anxiety 101 – a Review

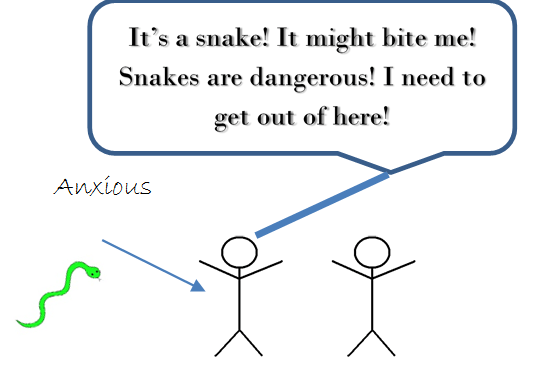

Anxiety is the product of perceiving a threat to something we value. In the simplest terms, when we believe there is a bear (a threat) in the bush near us (something we value) our body gets ready to run/fight/or freeze (anxiety). This simple formula can take far more advanced forms because we can value other things besides our own physical health and threats can take many forms beside that of a bear. While threats and things we value can take many forms, our bodies only have a small number of responses. These responses are run, fight, or freeze and we interpret our bodies getting ready to do these things as anxiety. For example, public speaking is perceived to be a threat to our goal of being perceived as competent and confident, taking a test poses a threat to our hopes of completing a class with a particular grade, and running out of gas threatens our goal of getting where we want on time. Our bodies will get ready to deal with all of these threats in the same ways – by making us anxious.

An Available Heuristic

If we accept this formula as an explanation for why we get anxious, this leads to another reasonable question: How do we decide how much of a threat something is? Tversky and Kahneman provide us with an answer but first let’s consider some other questions:

- When considering all of the words in the English language, which are three or more letters, are there more words with the letter K as the first letter, or more words with the letter K as the third letter?

- What percentage of middle aged men will have a heart attack?

- How honest are you?

To answer these questions our minds could use a number of different strategies. Our minds could list every known English word that is 3 or more letters, then compare how many begin with K and how many have K as the third letter. Even if we used this exhaustive and thorough strategy, our answers would be imperfect because we do not know every English word so we would be guessing based on the words we do know. As for the questions about heart attacks and honesty, we would never truly know the exact values because we are not omniscient and honesty is not something you can quantifiably measure. However, most people do not find it difficult to come up with answers to all of these questions. In fact, people tend to come up with answers extremely quickly.

When we are asked questions like these, our minds take the question we have been asked then quickly replace this very difficult question with a simpler question like “How easily can I remember or imagine something like this?”

If you are like most people, when asked the question about the letter K, you tried to think of words that begin with the letter K or had K as the third letter. If you could easily recall words beginning with K, but had greater difficulty thinking of words with K as the third letter, you concluded there must be more words beginning with K. Words with K tend to be easier to recall and most people assume there are more words beginning with K, even though there are more words with K as the third letter in English. Instead of being able to provide the true likelihood of heart attacks, our mind replaces this question with something like “How easily can you remember or imagine a middle aged man having a heart attack?” Then finally, you likely replaced the question about honesty with “How easily can I remember situations in which I was honest and dishonest?” It is not about how many memories we have being honest or dishonest, we form our judgments on the availability of those memories. Memories we can easily recall are said to be more available to our conscious minds than memories that are difficult to recall.

This mental “trick” is called the “availability heuristic.” As Tversky and Kahneman explain in their 1974 article, “There are situations in which people assess the frequency of a class or the probability of an event by the ease with which instances or occurrences can be brought to mind” (p. 1127). In other words, we believe something to be more likely if memories or fantasies of similar situations are “available” to our conscious mind. Most of the time the availability heuristic serves us pretty well. If something frequently happens in our life (the sun comes up every morning), one can assume it is likely for it to happen again without many costs being associated with this prediction. This allows us to avoid living in a constant state of uncertainty, predict what is likely to happen in the future, and plan accordingly. Unfortunately, the availability heuristic can be biased and sometimes this can have serious adverse consequences.

The availability heuristic is disproportionately influenced by recent and emotionally salient situations. Following a traumatic experience, people are far more likely to overestimate the probability of a similar traumatic event happening which artificially inflates our perceptions of how threatening a situation is, which in-turn unnecessarily increases anxiety and distress. Following a car accident, you will likely overestimate the likelihood of being in another car accident, which increases anxiety while driving. Following 9/11, many of us felt a new anxiety we did not previously experience while getting on air planes, not because flying was anymore dangerous (flying had probably never been safer than after 9/11) but because memories and fantasies of planes being high jacked were far more available.

Mental Process Underlying Mental Health Challenges

We determine which situations are threatening not by assessing the true threat level, but by assessing how easily we can remember or imagine similar situations ending-up poorly. Panic disorder can manifest in a number of ways, everyone is different, but people with panic disorder tend to worry that bodily sensations (heart arrhythmias, increased heart rates, accelerated breathing, dizziness, sweating, etc.) are evidence of a serious catastrophe (heart attack, stoke, going insane, etc.) which escalates anxiety resulting in panic attacks. Once we’ve had a single panic attack, the memory of this experience can be particularly available because panic attacks are so emotionally distressing. If we have had a panic attack in a store, we might later wonder about the possibility of having a panic attack in another store like Walmart. This question about the probability of having a panic attack in that particular Walmart at that particular time is replaced with “How easily can I imagine having a heart attack in Walmart?” If the answer is “very easily” then, we will assume the likelihood of having a panic attack in Walmart is high and we will likely avoid Walmart to avoid having another panic attack.

In obsessive-compulsive disorder (speaking of true OCD not the “OCD” people claim to have when they have strong preferences for cleanliness or organization), people can grossly overestimate the likelihood of someone breaking into their home and murdering their family because this specific fantasy can be incredibly distressing. When a fantasy is emotionally distressing, it is more available to consciousness, and this availability inflates perceptions of likelihood. Put simply, because the obsession is so upsetting, people will think it is likely, and they will act compulsively to reduce the probability of the feared event occurring.

In addition to anxiety disorders, the availability heuristic also plays a role in the development and maintenance of other mental health challenges. People with eating disorders often worry that people will judge them negatively if they were “fat.” They sometimes have vivid fantasies of being publically ridiculed or rejected for having what most people would consider to be an average or even below average weight. The maintenance of an eating disorder is riddled with availability heuristic errors. Often people will be able to easily imagine people judging them for being “fat” because they themselves frequently judge other people as fat and they take this as evidence suggesting other people have similar thoughts. The memory of their own judgments will be available because they are so frequent and this will inflate their perception about the likelihood of other people being judgmental like themselves. There are often historical traumas in childhood in which the person with the eating disorder was indeed bullied, mocked, and/or criticized, sometimes by close loved ones. While memories of this abuse are no longer recent, they may be incredibly available because of their emotional salience. They may also judge themselves as inadequate because they can easily recall examples of “beautiful” celebrities which inflates their perception of the regularity of these “beautiful” people.

When we are depressed, we will often have negative automatic thoughts about ourselves like “I’m a failure” or “I’m a loser.” Our minds will form these judgments by seeing which memories are most available, so if we can easily recall examples of “failures” or “losing”, we will be more likely to make judgments consistent with these memories. Since we tend to feel negative emotions more intensely than positive emotions, memories involving failure and loss may be easier to recall, and so these memories bias the availability heuristic and negatively distort our judgments.

Help is Available

The availability heuristic seems to be at the heart of many mental health challenges and this has some interesting implications for the treatment of mental illness. The availability heuristic is biased by recent and emotionally evoking memories and being aware of these biases allows us to think critically about the assumptions we make. In his 2011 book “Thinking, Fast and Slow” Daniel Kahneman explains “Resisting this large collection of potential availability biases is possible, but tiresome. You must make the effort to reconsider your impressions and intuitions by asking such questions as, ‘Is our belief that thefts by teenagers are a major problem due to a few recent instances in our neighborhood?’ or ‘could it be that I feel no need to get a flu shot because none of my acquaintances got the flu last year?’ Maintaining one’s vigilance against biases is a chore – but the change to avoid a costly mistake is sometimes worth the effort” (p. 131). This method of monitoring and thinking critically about our assumptions is identical to the cognitive restructuring interventions used in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy.

In addition to cognitive restructuring, exposure based therapies may also be used to combat the biases of the availability heuristic. It’s no surprise that people tend to avoid anxiety provoking situations. As Dr. David Burns explains in his book When Panic Attacks:

Most people who are anxious avoid the things they fear, so they never experience enlightenment or relief. If you’re afraid of heights, you’ll avoid high places because they make you feel dizzy and anxious. If you’re shy, you’ll avoid people, because you feel so insecure and inadequate. The avoidance fuels your fears, and your anxiety mushrooms. If you want to be cured, you’ll have to face the thing you fear the most. There are no exceptions to this rule. (Pp. 252-253)

Imagine a person who has a panic attack on an elevator. Following this experience, when the person’s mind attempts to calculate how dangerous a particular elevator is, it will not be calculating the true risk of taking the elevator because this is truly unknowable for every elevator in the world at any given time. It’s not like their mind will know there is a 1.2496% chance something goes wrong if they get in that elevator right now and remain in it for 28 seconds. Instead, they will replace the question, “How dangerous is this elevator?” with “how easily can I recall having an uncomfortable emotional experience in situations similar to what I imagine it is like to be in that elevator?” The memory of their last panic attack in the elevator will be very available because it is so emotionally evoking, even if it is not recent, and so the person will conclude getting on the elevator will be very dangerous. However, if the person decides to go into the elevator, even though they feel anxious, there is very little chance anything will go wrong. They will likely feel anxious and perhaps even have another panic attack, but after a few minutes this anxiety will dissipate. If they stay until their anxiety is gone, they may even feel pride and excitement about their achievement. Let’s say they repeat this exposure exercise 5 or even 10 times. The next time they wonder about how dangerous it is to get on an elevator, the memories of taking the elevator with nothing bad happening will be far more available and they will conclude the elevator is likely safe.

I recommend combining both of these cognitive and behavioral (exposure) approaches. Be mindful of how and why your mind is making the predictions and judgments it is making, but also go and have positive experiences to replace the negative memories creating these predictions and judgments. As you change your assumptions, predictions, and judgments through cognitive restructuring and exposure, you’ll experience serious emotional changes.

To be thorough, lets consider an example in which a person is depressed. As mentioned above, people who are depressed frequently experience negative judgments and predictions. We can fight depression by identifying and thinking critically about these judgments and predictions. So when we tell ourselves things like “I really can’t do anything right” we notice these thoughts and write them down, or record them in some way. Writing down our thoughts is a great way of distancing ourselves from what we are thinking. Then we think critically about these thoughts by simply asking some questions like “What memories is my mind accessing when I think I can’t do anything right? Are there other examples of me doing things reasonably well that my availability heuristic is ignoring? I put my pants on today correctly, is that not an example of doing “anything” right? So if I have done somethings right, like putting on pants, what do I really mean when I think I can’t do anything right? Do I mean that I have some regrets and if so, how do I know I have more regrets than other people? Even I have done more regretful things, what can I do about it? What is the value to ruminating on these regrets?” So this is one example of a cognitive restructuring technique called Socratic Questioning.

To combine our cognitive restructuring with a behavioral technique to combat the biases of the availability heuristic, we might create a list of things we could do to have the experience of doing something right. To make this list we might ask, what are some things you would be proud to do? Things like hike a mountain, read a book, volunteer, get a job, take a class, or clean up a local park. Then the depressed person would go and do these things, even if they don’t feel motivated to do so (action comes first, motivation comes later). The person would take photos of how they did and this would serve as evidence to dispute future thoughts about not doing anything right. Combining both these cognitive and behavioral approaches will help the person to become less depressed over time by combating the availability heuristic’s biases for emotionally evoking and recent memories.

Summary

To summarize, the availability heuristic is a mental process we use to make predictions and judgments. While it frequently helps us make complex decisions effectively, it is also biased to overemphasize recent and emotionally salient memories and fantasies. Unfortunately, these biases can create and maintain challenges like anxiety and depression. Cognitive restructuring and exposure techniques can help us challenge the underlying thinking which contributes to these problems.

Postscript

I’ve been studying the work of Tversky and Kahneman for several months now, beginning with the Michael Lewis book “The Undoing Project” which tells the amazing story of how they changed the world of psychology, economics, health care, finance, marketing, and so many more fields. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases is a brilliant 7-page article that can be found for free – click here. Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow is a fantastic insight into our minds and how they work.

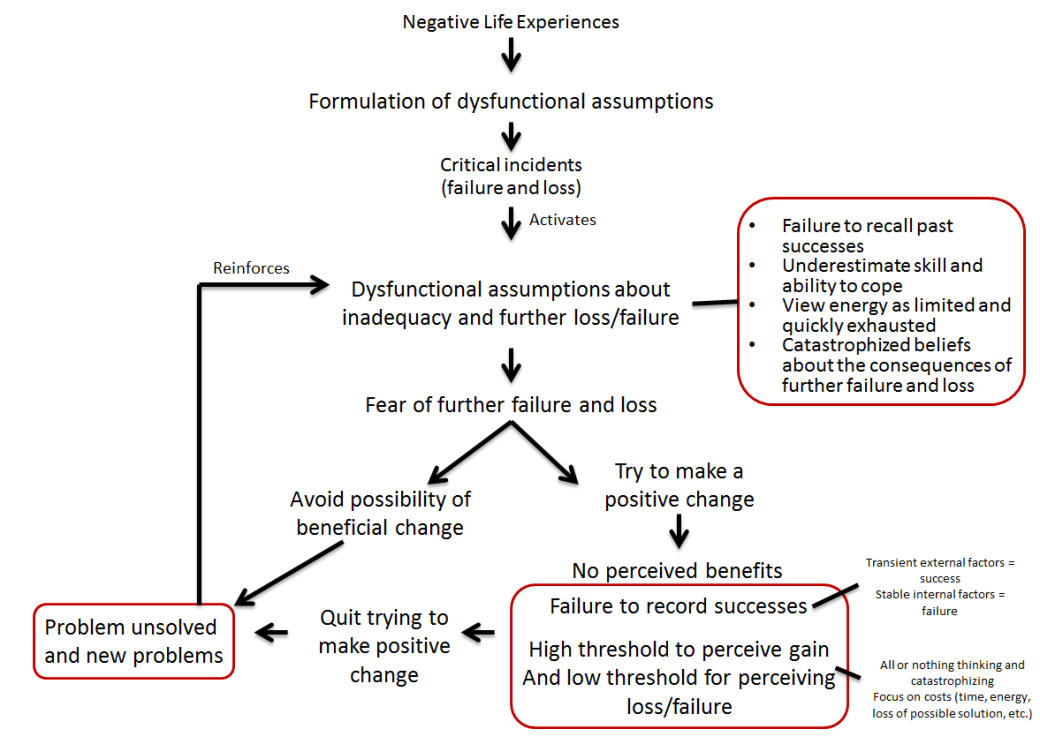

the assumptions that they are truly inadequate losers, others are a source of rejection and criticism, and they will inevitably fail and end up in unsatisfying relationships or be abandoned. Our dysfunctional assumptions become triggered by critical incidents (losses, failures, criticism, rejection, etc.) and this results in negative automatic thoughts (“I’m a loser”, “why can’t I do anything right”, “I’m going to end up alone”, “I have no real friends”, etc.). These negative automatic thoughts lead to extreme emotional responses (sadness, hurt, guilt, anxiety, etc.) which then leads to exaggerated behavioral responses (withdrawing, isolating, defensiveness, people-pleasing, conserving energy, etc.). We describe this combination of unhelpful and distressing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as depression.

the assumptions that they are truly inadequate losers, others are a source of rejection and criticism, and they will inevitably fail and end up in unsatisfying relationships or be abandoned. Our dysfunctional assumptions become triggered by critical incidents (losses, failures, criticism, rejection, etc.) and this results in negative automatic thoughts (“I’m a loser”, “why can’t I do anything right”, “I’m going to end up alone”, “I have no real friends”, etc.). These negative automatic thoughts lead to extreme emotional responses (sadness, hurt, guilt, anxiety, etc.) which then leads to exaggerated behavioral responses (withdrawing, isolating, defensiveness, people-pleasing, conserving energy, etc.). We describe this combination of unhelpful and distressing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as depression.