Exposure Therapy and Behavioral Experiments

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is the most validated form of therapy for anxiety disorders. In a huge review of studies exploring the effectiveness of CBT, the researchers found “The efficacy of CBT for anxiety disorders was consistently strong” (click here for a link to a free copy of this study). In another comprehensive review of studies exploring CBT for generalized anxiety, the authors concluded “when compared to waiting list control groups, these treatments have large effects on worrying, anxiety and depression, regardless of whether effects were measured with self-report measures or with clinician-rated instruments” (click here for a copy of this study). Many people would prefer their anxiety just went away but research suggests few people who do nothing, reduce their anxiety. As the studies above suggest, one of the things people can do to reduce their anxiety is cognitive-behavioral therapy and at the core of CBT for anxiety is exposure therapy and behavioral experiments.

Exposure therapy:

Simply put, exposure therapy involves exposing the client to their feared situations in a gradual, repeated, and prolonged manner until the client becomes desensitized. For example, if a client is terrified of public speaking they may work with their therapist to create a list of anxiety provoking situations (speaking in class, watching videos about public speaking, taking a class on public speaking, imagining speaking in public, speaking in a meeting at work, talking to a cashier at a store, doing a speech at Toastmasters, etc.). The client then ranks these situations from least anxiety provoking to most anxiety provoking, this is called an anxiety hierarchy. Then starting with a situation that does evoke some anxiety but is not overwhelming, the client would repeatedly expose themselves to these situations, over and over, until they become desensitized to this situation. A useful example of this most people can relate to is learning to swim as children. Many children are afraid or at least tentative about the water, but their parents encourage them to become more comfortable over time, often enrolling them in swim classes. As the child is gradually exposed to the water over time, they become less afraid. Alternatively, the children that are terrified of the water, and refuse to ever go in the water continue fear the water.

*For more information about exposure therapy see my article “Overcoming Anxiety and Avoidance” by clicking here, or download our free anxiety workbook by clicking here.

Behavioral experiments:

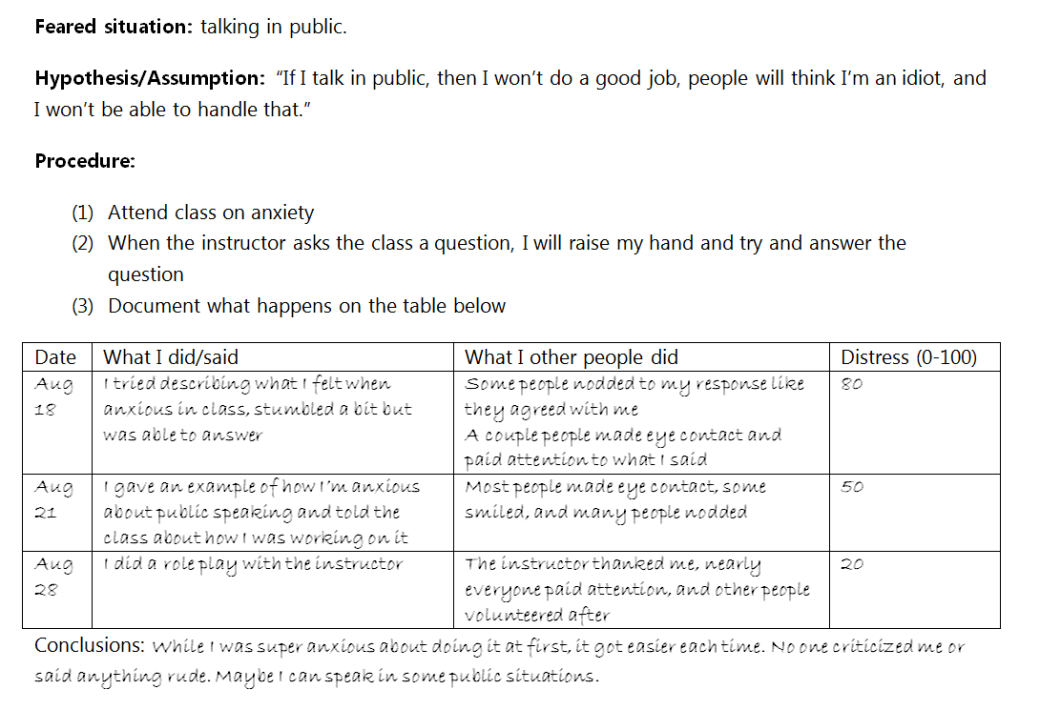

Behavioral experiments can take a number of different forms. Similar to exposure therapy, the client and therapist may work together to create a list of anxiety provoking situations. Then the client and therapist will work together to identify the client’s fears about what could go wrong in these situations. Often these fears are exaggerated and extreme but the client sees them as perfectly reasonable. So then we create a little experiment in which the client enters the feared situation and observes to see if their fears come true. Then the client runs the experiment several times in an attempt to gather more information. Once the client has run the experiment several times, they reconvene with the therapist to discuss what they have learned about their fears and their abilities to cope.

For example, perhaps one of the situations on the client’s anxiety hierarchy is saying “no” to other people. Perhaps the fear in this situation is something like “If I say no to my mother when she asks me to do something, she will call me selfish, the rest of my family will hate me, and I won’t be able to handle that.” So then the client and therapist run an experiment in which the client talks with their mother, explains they are trying to be more assertive and wants to work on saying “no” sometimes. Then the next time their mother asks them to give them a ride to the store, the client explains they cannot help that day due to other commitments, then observes what happens. In this situation, the client’s mother may very well call the client “selfish” and their family may complain, but the client also learns they can survive being called selfish and occasionally listening to complaints. Or perhaps the client’s mother understands the client has other commitments and they schedule a plan in which the client gives their mother a ride another time, or the client’s mother finds another way to the store. See the below table for an example how I would write-up a behavioral experiment assignment with a client.

Another type of behavioral experiment involves the client identifying what they suspect other people believe then conducting a survey to assess the accuracy of the client’s assumptions. For example, the client may believe that people believe that women over a particular weight are “unattractive.” Clients may start by simply ask some trusted friends or family about this assumption. They may take photos of themselves or others to friends or family and ask people about their impressions about the people in the photos. In this example, the client ideally learns that attractiveness is not directly related to something as arbitrary and simplistic as weight.

How it works:

In my experience, exposure therapy and behavioral experiments have been immensely helpful for clients. Clients usually report dramatic shifts in their anxiety in only a short period of time. In CBT we assume the client becomes less anxious in situations they are exposed to because they learn that their initial assumptions about the dangerousness of the situation is exaggerated and their beliefs about their abilities to cope with the danger posed by those situations is minimized. In other words, their cognitions change. After exposing themselves to a variety of different situations, the client learns they have a habit of exaggerating danger and minimizing their abilities to cope, and so they become less anxious in other situations they have not exposed themselves too.

For example if you are anxious about travelling but you muster the courage to go to Mexico, you might learn that Mexico isn’t as dangerous as you expected. Then if you go to Germany you might learn that Mexico and Germany are safe. Then if you go to India you might learn that Mexico, Germany, and India can be travelled to safely. Then you might learn that travelling in general can be done safely, not only to those countries you have been to in the past.

Challenges:

One challenge in using exposure and behavioral experiments is explaining the importance of actually facing fears to the client. Some clients have spent decades avoiding situations that make them anxious and the thought of deliberately exposing themselves to these situations is terrifying. People tend to want to avoid situations that make them anxious. Unfortunately, it is this very avoidance which perpetuates the anxiety indefinitely.

Another barrier to effective exposure and behavioral experiments is called “safety behaviors.” Safety behaviors can sometimes resemble the compulsions of someone who struggles with OCD. Safety behaviors are unnecessary, excessive, or unhelpful activities or strategies people use in anxiety provoking situations to protect them from “something going wrong.” When the client is anxious about going to a new restaurant they may excessively research the restaurant online to create a plan to prevent something “bad” from happening. In this example the excessive research is the safety behavior the client uses to keep themselves “safe.” Then when they go to the new restaurant and nothing “bad” happens they convince themselves it is because they researched prior to going. In this situation, the client has not learned that they can safely go to a variety of different restaurants, but instead they have learned they can go to a restaurant when they excessively research it in advance. Other examples include holding glasses very tightly when you’re afraid of spilling, distracting yourself with your phone when afraid of standing in lines, and never disagreeing with people when you are afraid of conflict. Research suggests it is imperative safety behaviors are identified so the client can either avoid using them or gradually reduce the use of safety behaviors over time.

Sometimes a client’s anxiety is about situations to which they cannot be exposed. For example, the client might be terrified of earth quakes, someone dying, their son being in a car accident, getting fired, or being homeless. When the client cannot be directly exposed to their feared situations, we have got to get creative. We can watch videos of these situations, we can do research, we can read stories, we can write then recite our own stories in which the client is exposed to these situations, etc. This is based on the idea that thinking about the feared situation can actually desensitize the client. Some of these interventions are called “imaginal exposure.”

Conclusions:

Research suggests CBT is an effective treatment for anxiety disorders. Exposure therapy and behavioral experiments are core elements of CBT for anxiety. By facing fears the client learns their feared situations are not as catastrophic as originally predicted and their ability to cope is better than expected.

talking to authority figures, you would likely experience anticipatory anxiety before you spoke to people of authority, then when you did have to talk to someone of authority (exposing yourself to the feared situation) your anxiety would likely spike. Then when you avoid the situation by promptly leaving, your anxiety will naturally go down. Unfortunately, when we cope with anxiety by avoiding challenging situations we cannot challenge our assumptions that the situation is dangerous, we cannot challenge our assumptions that we cannot handle the stressful situation, nor can we learn how to handle the situation more effectively. So then the next time we exposure ourselves to the stressful situation we experience a similar amount of anxiety.

talking to authority figures, you would likely experience anticipatory anxiety before you spoke to people of authority, then when you did have to talk to someone of authority (exposing yourself to the feared situation) your anxiety would likely spike. Then when you avoid the situation by promptly leaving, your anxiety will naturally go down. Unfortunately, when we cope with anxiety by avoiding challenging situations we cannot challenge our assumptions that the situation is dangerous, we cannot challenge our assumptions that we cannot handle the stressful situation, nor can we learn how to handle the situation more effectively. So then the next time we exposure ourselves to the stressful situation we experience a similar amount of anxiety.