You never listen to me. I fell like you are overreacting. I can’t do anything right, I’m always the bad guy. Don’t get upset. You always do this. You’re an asshole. Why do you have to be such a bitch? This is why this shit always happens to you.

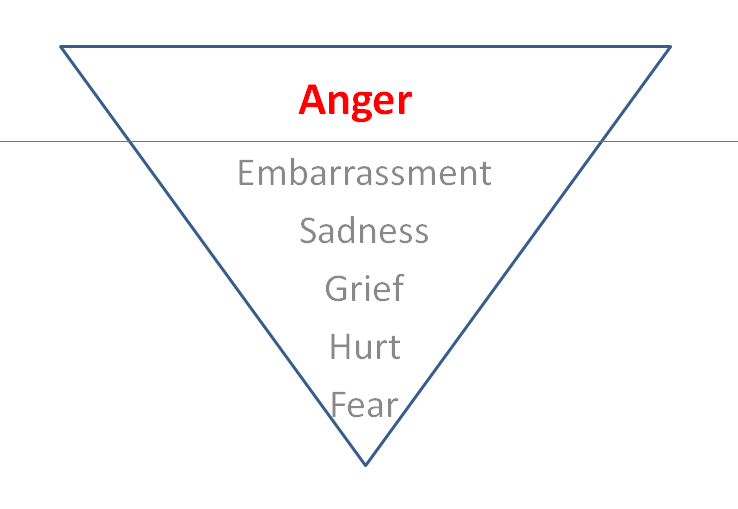

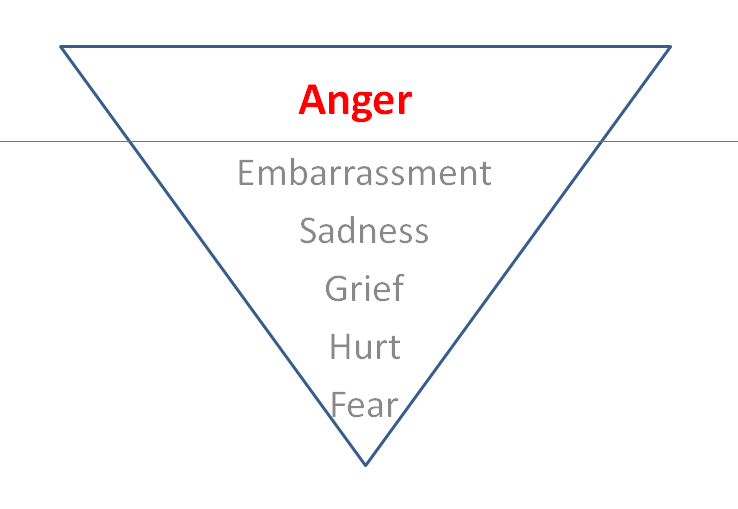

Have you ever been hanging out with friends and have the displeasure of watching another couple’s argument turn into a full-blown fight? Have you ever been shocked by the devastatingly hurtful things family members say to each other? I’ve both been the shocked observer and I reluctantly admit to having been one of the people saying the hurtful things. On the surface, these statements appear to be motivated by anger. However, anger is described as a “surface emotion” and underneath anger there is usually a more vulnerable emotion like hurt, sadness, embarrassment, grief, etc.

Our angry behavior (yelling, intimidating, saying hurtful things) can be a way of communicating more vulnerable emotions. Unfortunately, communicating in this way is inherently manipulative because we are not communicating directly about what is going on for us. Instead of using the words “when you said I was lazy, I felt hurt because I really value your opinion. I also felt afraid because I was concerned you might not want to be in a relationship with someone you think is lazy”, we hope they get some form of this message through our angry behavior.

Our anger can also serve as a tool to teach another person about what we want. People learn through processes like reinforcement, punishment, and extinction. When another person does something we don’t like, we can use anger to punish them, in hopes they will not replicate this behavior in the future. For example, when Person A says something hurtful (you’re lazy), Person B may retaliate to punish the other person to reduce the probability of future hurtful comments. However, when we are in a relationship with a person and they are continuously punishing us we are likely going to develop resentment because, by definition, people don’t like being punished. So while anger can be a powerful form of punishment, it can seriously poison a relationship.

Holding on to anger is like grasping a hot coal with the intent of throwing it at someone else; you are the one who gets burned. – Buddha

One of the best examples of these two concepts is when we get angry about another person getting angry. Getting angry at another person for getting angry at you is like trying to put out a camp fire with gasoline. Person A gets mad, then Person B thinks something like “I don’t deserve to be treated like this!” and gets angry to punish Person A. In addition to feeling anger, Person B is also probably feeling fear, hurt, and maybe even embarrassment.

If you have the goal of intimidating someone, expressing anger in an aggressive way may move you closer to achieving your goal. However, if you have the goal of having a good relationship with the other person, expressing anger in an aggressive way will be less helpful.

So how do we reduce the likelihood we will get extremely angry and how do we communicate better when we are angry?

Reducing the likelihood of getting extremely angry. CBT recommends we begin by identifying our “triggers” and times when we are more likely to become triggered. “Triggers” are things (people, comments, situations, etc.) that rapidly increase our emotional responses. For example, if you are triggered by criticism, you are likely to have an extreme emotional response to being criticized. Common triggers include perceived rejection, failure, abandonment, and loss. Identifying your triggers in advance is a form of exposing yourself to your triggers through the use of your imagination. This “imaginal exposure” actually can reduce how distressing these triggers will be when you are exposed to them in real life. Furthermore, identifying your triggers in advance allows you to plan how you want to respond when faced with this trigger.

We are more likely to be triggered in certain circumstances. For example, I am more likely to be triggered when I am tired, hungry, or while drinking alcohol. So I make reasonable attempts to avoid situations that may trigger me during times when I’m more likely to become triggered. For example, if I have to talk to a friend about a sensitive topic, I do so when I’m rested, fed, and sober.

These two principles of identifying triggers in advance and considering times when we are more likely to become triggered can be useful for managing all extreme emotions, not simply anger.

Regardless of whether or not we identify triggers and times we are more likely to be triggered, we may still get triggered unexpectantly. While there are a ton of relaxation skills out there, some are more effective than others. These are the ones I recommend to people managing intense anger.

Minimize risk. Stop yourself from the “knee-jerk” reaction that often accompanies anger. Then I recommend you remove yourself from the situation if it is reasonably possible, it may also be useful to say something like “I don’t mean to be rude but I have to go calm down for a moment” and go for a walk.

Relax the body. Then cool off by splashing cold water on your face, taking a cold cloth and putting it on your face or the back of your neck, or taking a cold shower. You’ll learn that it is really difficult to stay mad when your face is frozen. Take some breaths, one useful breathing exercise is the 4-7-8 breath where you breath in for 4 seconds, hold your breath for 7 seconds, and breath out slowly for 8 seconds. Intense exercise and something called “progressive muscle relaxation” also can be very effective for calming our bodies.

According to Baranowsky, Gentry, and Schultz (2011, p. 127), when our fight/flight/freeze response is activated we are using our “sympathetic nervous system” and when we are calm we are using our “parasympathetic nervous system.” When the sympathetic nervous system parts of our brain are dominant our thinking is reactive, we have an increased threat perception, and we have diminished brain functioning. By contrast when the parasympathetic nervous system parts of our brain are dominant, we are more capable of creative problem solving, we have better decision making, and we are better at regulating our emotions. By relaxing our bodies we can shift from sympathetic nervous system dominance to parasympathetic dominance.

Calm down the mind. Once our bodies are calm, we are more capable of communicating and problem-solving. We can use cognitive-restructuring strategies to identify the thoughts causing our intense emotional reactions, challenge the validity of these thoughts, and replace them with more realistic thoughts. The automatic thoughts commonly associated with intense anger include thoughts about fairness (How dare you call me a jerk after all I do for you! I don’t deserve this!) and about how we want people to behave (You shouldn’t be acting like this! I should better at this! You should take out the trash!).

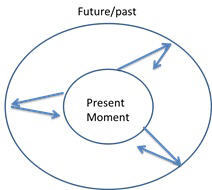

We can also use mindfulness skills to calm our mind. Put simply, when using mindfulness we are paying attention to what is going on in our mind, without judgement. We notice, accept, and let go of our anger inducing thoughts. It sounds simple but it takes practice.

Communicate. Once our bodies and our minds are calmer we may choose to communicate. Some good skills for communicating assertively include “I-messages” and the “assertive message format.”

I-messages typically include a description of how we feel, explaining the reasons for this emotional response, and clearly describing what you want. Some examples:

I felt angry when you said that I never listen to you, I’d like to talk about this.

I felt concerned when you raised your voice earlier, I’d appreciate if you could avoid doing that in the future.

I felt sad and surprised when you said my family is crazy, I’d like to understand where that comment came from.

The assertive message format includes: a description of behavior, an interpretation, describing your emotions, consequences, and your intention/position. These components can be combined in any order.

You were running behind yesterday and (behavioral description), as a result we were late to meet up with everyone (Consequence), I’m sure you didn’t mean to be late but (interpretation), and honestly, I was feeling a little annoyed and frustrated (feelings), next time, I would appreciate it if you could toss me a text if you’re running behind (intention/position).

“We can say what we need to say. We can gently, but assertively, speak our mind. We do not need to be judgmental, tactless, blaming or cruel when we speak our truths”

― Melody Beattie

Both I-messages and the assertive message format are designed to open a dialogue with the other person, while reducing the probability they will respond defensively. When using these skills it is important to avoid blaming (you are responsible for your own emotional reactions), generalizing (“You’re always late”), or name calling. I’ll revisit more communication skills in future posts.

To summarize, anger is a surface emotion, usually with more vulnerable emotions underneath. Anger can be used to communicate more vulnerable emotions as well as punish other people to behave in ways that we want. We can reduce the likelihood of becoming extremely angry by identifying our triggers and times when we are more likely to become triggered. When we do become angry, we can manage our anger by reducing the risk, calming our bodies, calming our minds, and communicating effectively in a respectful and compassionate way.

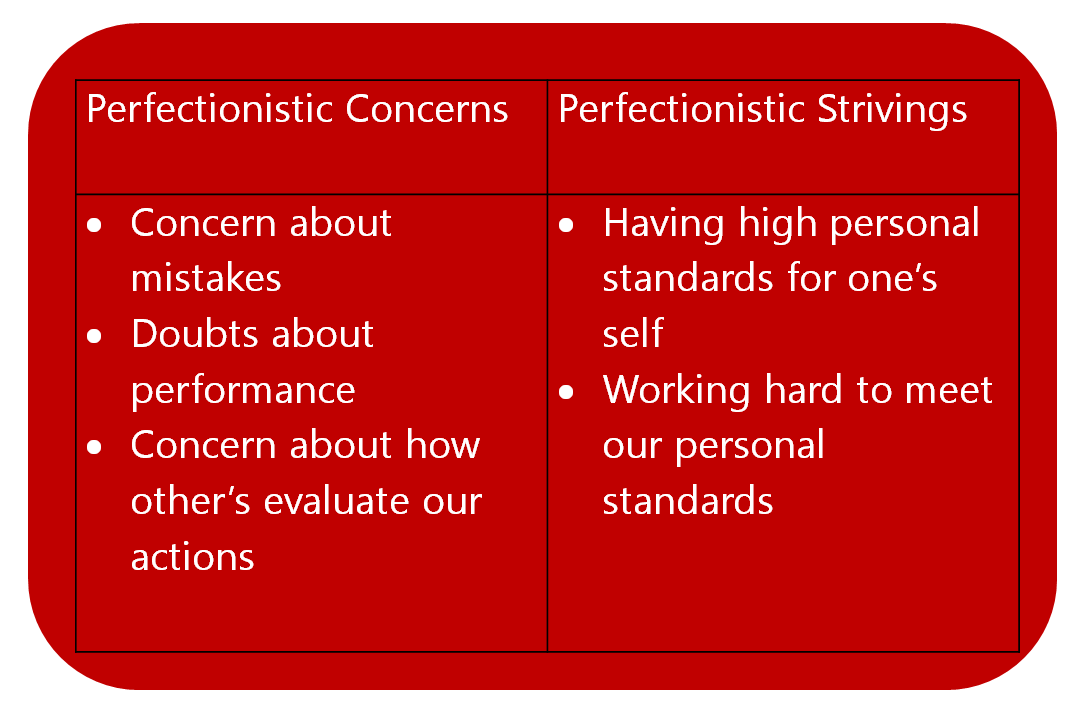

mindfulness based theories, CBT, etc.) all have underlying philosophies about how human beings “work”, what is “healthy”, and how people can remove barriers to become more “healthy.”

mindfulness based theories, CBT, etc.) all have underlying philosophies about how human beings “work”, what is “healthy”, and how people can remove barriers to become more “healthy.”  reasons. People tend to want to minimize their choices and responsibility by suggesting they have no control over what they think or feel. There are several old videos of Albert Ellis working with clients on YouTube, and he has a very direct and almost confrontational style that I believe is reflected in the uncompromising philosophy of RET (

reasons. People tend to want to minimize their choices and responsibility by suggesting they have no control over what they think or feel. There are several old videos of Albert Ellis working with clients on YouTube, and he has a very direct and almost confrontational style that I believe is reflected in the uncompromising philosophy of RET (

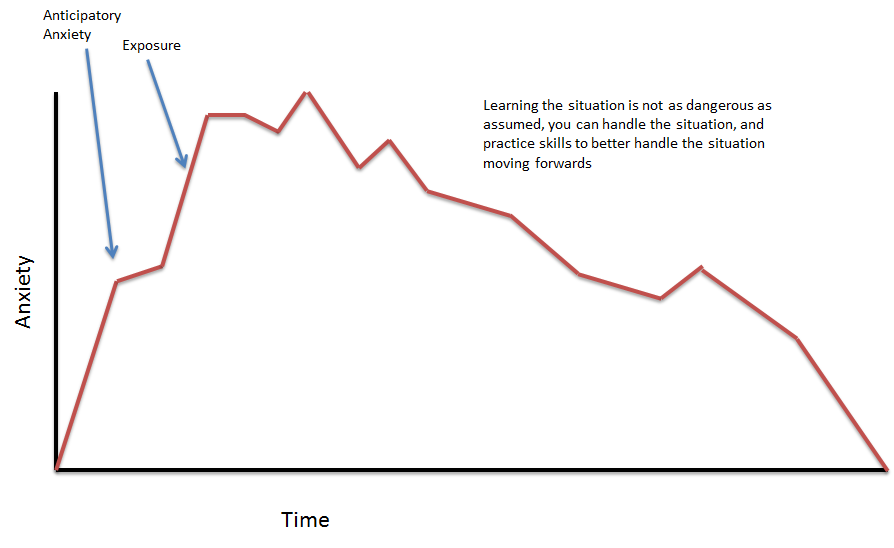

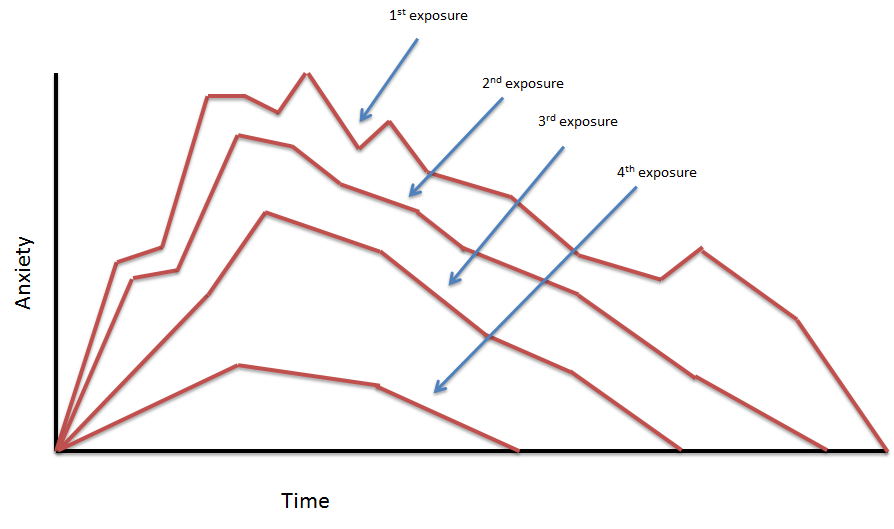

talking to authority figures, you would likely experience anticipatory anxiety before you spoke to people of authority, then when you did have to talk to someone of authority (exposing yourself to the feared situation) your anxiety would likely spike. Then when you avoid the situation by promptly leaving, your anxiety will naturally go down. Unfortunately, when we cope with anxiety by avoiding challenging situations we cannot challenge our assumptions that the situation is dangerous, we cannot challenge our assumptions that we cannot handle the stressful situation, nor can we learn how to handle the situation more effectively. So then the next time we exposure ourselves to the stressful situation we experience a similar amount of anxiety.

talking to authority figures, you would likely experience anticipatory anxiety before you spoke to people of authority, then when you did have to talk to someone of authority (exposing yourself to the feared situation) your anxiety would likely spike. Then when you avoid the situation by promptly leaving, your anxiety will naturally go down. Unfortunately, when we cope with anxiety by avoiding challenging situations we cannot challenge our assumptions that the situation is dangerous, we cannot challenge our assumptions that we cannot handle the stressful situation, nor can we learn how to handle the situation more effectively. So then the next time we exposure ourselves to the stressful situation we experience a similar amount of anxiety.

ions throughout my day. What does practicing mindfulness look like? Take a breath, notice the air filling your lungs, notice your rib cage expanding, notice your heart beat, just notice how it feels. Focus on those things, and without judgment (“It should be deeper”, “it should be slower”, “it should be…”), just notice the way it is. Congratulations, you have just practiced mindfulness. It’s that simple.

ions throughout my day. What does practicing mindfulness look like? Take a breath, notice the air filling your lungs, notice your rib cage expanding, notice your heart beat, just notice how it feels. Focus on those things, and without judgment (“It should be deeper”, “it should be slower”, “it should be…”), just notice the way it is. Congratulations, you have just practiced mindfulness. It’s that simple.