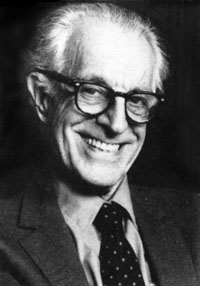

All counselling theories (narrative therapy, psychoanalysis, DBT,  mindfulness based theories, CBT, etc.) all have underlying philosophies about how human beings “work”, what is “healthy”, and how people can remove barriers to become more “healthy.” People might be surprised to know there are a number of different variations of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). One type of CBT is called Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET) and it was created by Albert Ellis. This article describes the underlying philosophies of RET and has been adapted from Bill Borcherdt’s book “Think Straight! Feel Great! 21 guides to Emotional Self-Control.”

mindfulness based theories, CBT, etc.) all have underlying philosophies about how human beings “work”, what is “healthy”, and how people can remove barriers to become more “healthy.” People might be surprised to know there are a number of different variations of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). One type of CBT is called Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET) and it was created by Albert Ellis. This article describes the underlying philosophies of RET and has been adapted from Bill Borcherdt’s book “Think Straight! Feel Great! 21 guides to Emotional Self-Control.”

RET is designed to teach people:

1. Feelings are not externally caused.

- Our emotions and moods are caused by our thinking, not what happens to us, what others say, or our environment. We interpret the things that happen to us, and our emotions are caused by these interpretations. This is important because you can learn to control what you think and when you can do this, you can control how you feel.

2. Dissatisfaction is not the same as disturbance.

- Things will inevitably frustrate, deprive, and inconvenience you, but you disturb yourself by insisting that dissatisfactions should not exist.

3. All rejection is self-rejection and is self-inflicted.

- People may evaluate you and choose to not associate with you, but your feelings of embarrassment, shame, anxiety, and sadness are caused by your thoughts like “because this person does not want to associate with me, this means I’m no good!”

4. Recognize preferences are not demands.

- While it is normal to have preferences, emotional disturbances occur when we demand to have our preferences met.

5. Nothing “has to be.”

- You do not have to survive; you choose to survive because you want to survive. When we label “wants” as “needs” this creates desperation and a sense of urgency which can lead to distress.

6. Distinguish appropriate and inappropriate feelings.

- Intense emotions often get in the way of working towards our goals. It is normal to get frustrated, annoyed, disappointed, apprehensive, and sad but it is often unhelpful to become enraged, devastated, panicked, ashamed, and depressed.

7. Put yourself first and others in a close second without shame or guilt.

- This promotes happiness and joy, which can make you more fun to be around.

8. Avoid evaluating humans.

- Humans are too complex and ever-changing to judge or score. Neither yourself nor other people are simply “good” or “bad.”

9. Do the “right thing” for the “right reason.”

- Pursue goals and accomplishments because they provide you with happiness or some practical improvement to your life, rather than inflating your ego or providing you with approval from others.

10. Avoid overemphasizing change.

- Learn to co-exist with your problems and imperfections, rather than putting undue pressure of yourself to overcome all problems.

11. Attempt to get better, rather than merely feeling better.

- What feels good isn’t always good for us. For example, expressing intense unwanted emotions, like anger, might feel good at the time, but it might move us away from our life goals.

12. Abandon absolute thinking.

- Identify, challenge, and uproot these three core irrational ideas:

- “I must do perfectly well or I’m completely worthless,”

- “You must treat me perfectly, with no lapses in kindness and consideration, or you are completely worthless.”

- “Life must make it easy on me to reach my goals and accomplishments.”

I suspect people will see some common themes in these recommendations. Generally, RET emphasizes personal responsibility and choice, it suggests that we are responsible for our emotional reactions and we can change our emotions, by changing what and how we think. RET also recommends we unconditionally accept our “self” while judging our emotional reactions as “appropriate” or “inappropriate”, which I think is an interesting idea. While I do not choose to use this terminology with my clients, I agree that intense emotions can interfere with our attempts to achieve our goals.

Most clients are resistant to making changes in their lives, usually for a variety of different  reasons. People tend to want to minimize their choices and responsibility by suggesting they have no control over what they think or feel. There are several old videos of Albert Ellis working with clients on YouTube, and he has a very direct and almost confrontational style that I believe is reflected in the uncompromising philosophy of RET (click here for a classical example of RET at work). I’m not saying the advice listed above is bad advice, just that I suspect giving this advice in a way that clients could receive it non-defensively could take some tact.

reasons. People tend to want to minimize their choices and responsibility by suggesting they have no control over what they think or feel. There are several old videos of Albert Ellis working with clients on YouTube, and he has a very direct and almost confrontational style that I believe is reflected in the uncompromising philosophy of RET (click here for a classical example of RET at work). I’m not saying the advice listed above is bad advice, just that I suspect giving this advice in a way that clients could receive it non-defensively could take some tact.