The Jewish psychiatrist Viktor Frankl remembers the day he entered the camps:

Then the train shunted, obviously nearing a main station. Suddenly a cry broke from the ranks of anxious passengers, “there is a sign, Auschwitz!” Everyone’s heart missed a beat at that moment. Auschwitz – the very name stood for all that was horrible: gas chambers, crematoriums, massacres. Slowly, almost hesitatingly, the train moved on as if it wanted to spare its passengers the dreadful realization as long as possible: Aushwitz!

His book Man’s Search for Meaning tells a harrowing tale of some of the worst conditions humans have been exposed to in modern history. As I read this book for the first time, several years ago, I was mesmerized by Dr. Frankl’s seemingly endless ability to recognize the opportunities within his experiences. His beliefs about problems and suffering were infectious.

Negative Problem Orientation

Put simply, a person’s problem orientation refers to their beliefs about problems and their ability to solve problems. People with a negative problem orientation are more likely to view problems as excessively threatening, they typically doubt their ability to solve problems, and they believe negative outcomes will occur regardless of how much effort they put in to solve them. As a result of these beliefs, researchers Dugas and Robichaud suggest people with a particularly negative problem orientation are more likely to be frustrated, irritated, anxious, or depressed when they face a problem. Behaviorally, people with a negative problem orientation are more likely to procrastinate and/or avoid problem solving. As a result, they can make new problems for themselves and increase worries.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, negative problem orientation has been connected with a wide variety of mental health difficulties including generalized anxiety disorder, depression, pathological gambling, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Robichaud & Dugas, 2005).

Locus of Control

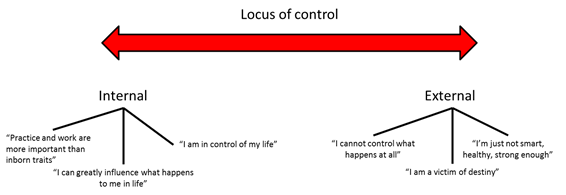

In my opinion, a person’s problem orientation plays a massive role in how they approach the world. There seems to be a large overlap between problem orientation and something, in psychology, we call “locus of control.” Our locus of control can be described as our beliefs about how much we influence what happens in our lives. People with an “internal locus of control” typically believe they greatly influence their destiny. While people with an “external locus of control” typically believe that what happens in their lives is largely controlled by forces outside of them. Research over the last 65 years has suggested that people with an internal locus of control have greater academic success, are more motivated, are more socially mature, have less stress and depression, and live longer. They “earn more money, have more friends, stay married longer, and report greater professional success and satisfaction” (Duhigg, 2016, p. 24). So to summarize, people with an internal locus of control will usually be less threatened by problems, work harder to solve problems, and believe they can mitigate negative outcomes through effective problem solving. In other words, they have a more positive problem orientation.

So if a negative problem orientation and an external locus of control are typically unhelpful for promoting health and wellbeing, what can we do to change?

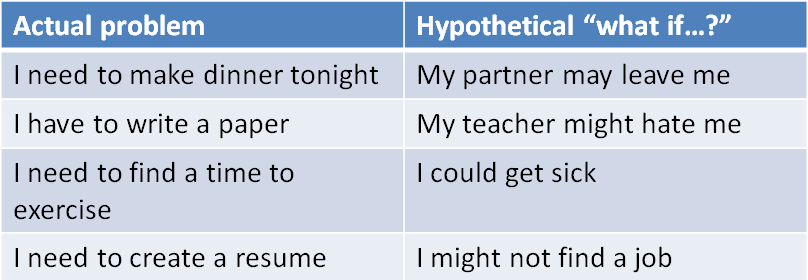

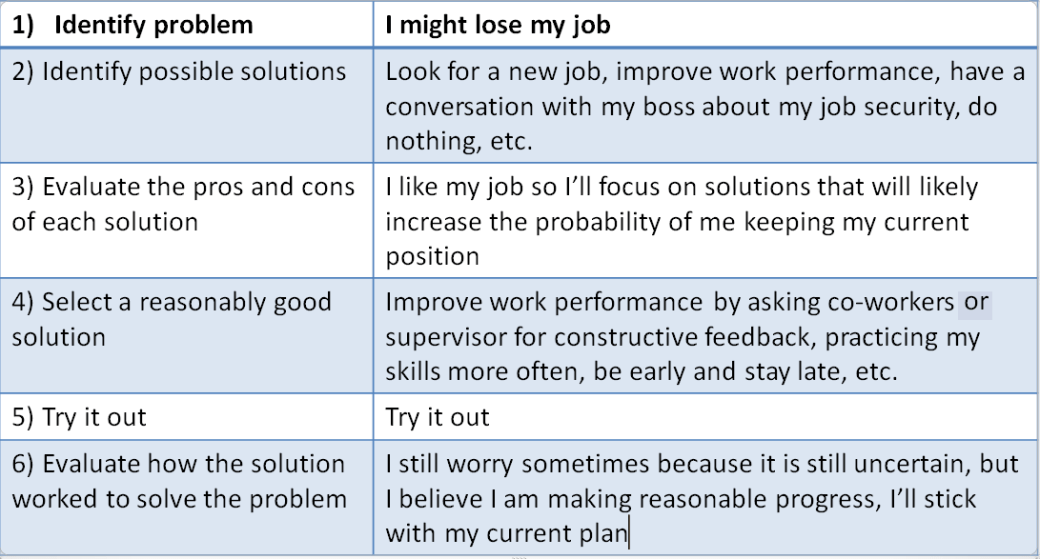

Luckily, research suggests there are a few things we can do to improve our problem orientation and our beliefs about locus of control. Dugas and Robichaud suggest we first have to learn how to identify problems. Many clients enter therapy and believe that their emotions are the problem, they just want to be happy. However, emotions are not the problem. Emotions are data, they are just information giving you clues something is or is not working for you in life. The problem is not that you are depressed, the problem may be you are stuck in a relationship that is not good for you, it could be that your habits are not particularly healthy, it might be that you are stuck in depressive thinking habits, perhaps the problem is that you are in a concentration camp, etc. Once we can see our emotions as information, this can help you identify appropriate solutions to the real problems.

The belief that we are exceptional because we experience problems can keep us stuck. Why does this keep happening to me? Why was I the one who was dealt a bad hand in life? We can improve our problem orientations by challenging these kinds of beliefs and recognizing that experiencing problems in life is normal. Suffering is an important part of life, it is times when we suffer the most that we are motivated to adapt and grow the most.

Challenge filtering and overgeneralizing (see our cognitive distortions list). An internal locus of control and/or a negative problem orientation occurs because we are not paying enough attention to all the times your effort and practice have influenced outcomes. We conclude because we could not have possibly prevented ____________ from happening in the past, why bother trying in the future? While there is a lot in life that you cannot control, there is a massive amount that you can. By just focusing on the things we cannot control, we are underestimating the number of choices we have. When we underestimate the choices we have, we are reinforcing the belief that we are not responsible for what happens to us and this can be a very comfortable delusion to live in. However, this short term comfort comes with a price, it disempowers us and maintains a victim mentality.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, we can improve our problem orientation by recognizing the opportunities that are within all of the problems we experience. Every problem has opportunities associated with it. Few people illustrate this better than Viktor Frankl. While in the camps, he became very sick, and with the sickness came a far greater likelihood of being “selected” to go to the gas chambers. Despite his sickness he remembers:

We were sick and I did not have to go on parade. We could lie all day in our little corner in the hut and doze and wait for the daily distribution of bread (which, of course was reduced for the sick) and for a daily helping of soup (watered down and also decreased in quantity). But how content we were; happy in spite of everything.”

This sickness gave him the opportunity to rest. More generally, by being a prisoner within the camp, Frankl recognized he was given the opportunity to study what happens to a human under such circumstances. He was given the opportunity to understand how people find meaning and purpose even in the worst of conditions. Gordon Allport describes Frankl’s conclusions beautifully in his preface:

In the concentration camp every circumstance conspires to make the prisoner lose his hold. All the familiar goals in life are snatched away. What alone remains is “the last of human freedoms” – the ability to “choose one’s attitude in a given set of circumstances.”

Being in the camp presented many, very real and horrifying, problems. However, Frankl was also given the opportunity to choose how he was going to cope with these problems. He was given the opportunity to search for answers to some very fundamental human questions – what prevents some men from committing suicide in such horrible conditions? Why choose to live when one can simple run to the electric fences at any time? What motivates a man to treat prisoners a particular way? Etc.

When your partner says something you don’t agree with, you are being given the opportunity to practice your non-defensive communication skills. When you lose a relationship you have the opportunity to be a kind, loving, and respectful person even when things do not go your way. When you get lost, you have the opportunity to become familiar with somewhere new. When you are in a concentration camp, you have the opportunity to study how humans adapt to such horrible conditions and find meaning and purpose despite great suffering.

If you have children, it is likely they will experience their own challenges in life (divorce, trauma, accidents, health problems, etc.) and every time you experience these things, you are being given the opportunity to teach your kids how to effectively face these problems in their own lives. By recognizing the opportunities within the problems we face, we are going to be more likely to accept when problems occur and we will be more motivated to engage with our problems in a helpful way.

Duhigg, C. (2016). Smarter, faster, better: The secrets of being productive in life and business. Doubleday Canada.

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. Washington Square Press, New York.

Robichaud, M., Dugas, M. (2005). Negative problem orientation (part I): Psychometric properties of a new measure. Behavior Research and Therapy (43)3, 391-401.