“You can take a horse to water but you can’t make them drink.”

There are many reasons people resist making positive changes in their lives. As a therapist, the number of reasons I’ve heard for not making a change is truly astounding. When I talk about this with people, they explain it’s obvious – people don’t make changes because they “fear change.” I’ve always found this explanation to be unsatisfying. It sounds like another example of people wanting a simple explanation for something complicated. Why do people fear change? What specifically about change do people fear? I tried to answer these questions by reading Robert Leahy’s “Overcoming Resistance in Cognitive Therapy.” From this book, others like it, and my own experiences, I have learned resistance does not interfere with therapy, overcoming resistance is the therapy. Most people have an idea of how they could make a positive change in their lives, but they typically resist making these changes. One of the most interesting chapters in Leahy’s book describes the “Investment Model of Resistance” and how it applies to people with depression.

The Depressive Paradox

When people are depressed they are less likely to engage with activities which would likely reduce their depression. Instead of problem solving, exercising, socializing, working, sleeping 8 hours, and eating a healthy diet, people with depression are more likely to isolate, withdraw, conserve energy, and avoid. This is referred to as the “depressive paradox.” When people are depressed, one would expect them to be more motivated to pursue pleasure and meaningful engagement. Like how a starving person becomes intensely motivated to acquire food. From this perspective, avoiding potentially rewarding and enjoyable experiences seems to make no logical sense. As opposed to accepting a person with depression is simply illogical and self-destructive, Leahy’s Investment Model of Resistance suggests people with depression are primarily motivated to avoid losses, failures, and rejections, as opposed to being motivated by the possibility of acquiring the potential benefits of making a change. Like how a person who is intensely afraid of losing money will turn down a great investment opportunity because they cannot tolerate even a minimal amount of risk. Leahy suggests there is an underlying logic to the decision making of a depressed person, but this logic is based on distorted assumptions and beliefs.

The Cognitive Model of Depression

Aaron Beck is one of the founding fathers of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Beck’s Cognitive Model of Depression is an immensely valuable contribution to our understanding of depression. Beck suggests negative life experiences result in the formulation of dysfunctional assumptions about the self, the world, and the future. For example, people with abusive or neglectful parents may develop  the assumptions that they are truly inadequate losers, others are a source of rejection and criticism, and they will inevitably fail and end up in unsatisfying relationships or be abandoned. Our dysfunctional assumptions become triggered by critical incidents (losses, failures, criticism, rejection, etc.) and this results in negative automatic thoughts (“I’m a loser”, “why can’t I do anything right”, “I’m going to end up alone”, “I have no real friends”, etc.). These negative automatic thoughts lead to extreme emotional responses (sadness, hurt, guilt, anxiety, etc.) which then leads to exaggerated behavioral responses (withdrawing, isolating, defensiveness, people-pleasing, conserving energy, etc.). We describe this combination of unhelpful and distressing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as depression.

the assumptions that they are truly inadequate losers, others are a source of rejection and criticism, and they will inevitably fail and end up in unsatisfying relationships or be abandoned. Our dysfunctional assumptions become triggered by critical incidents (losses, failures, criticism, rejection, etc.) and this results in negative automatic thoughts (“I’m a loser”, “why can’t I do anything right”, “I’m going to end up alone”, “I have no real friends”, etc.). These negative automatic thoughts lead to extreme emotional responses (sadness, hurt, guilt, anxiety, etc.) which then leads to exaggerated behavioral responses (withdrawing, isolating, defensiveness, people-pleasing, conserving energy, etc.). We describe this combination of unhelpful and distressing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as depression.

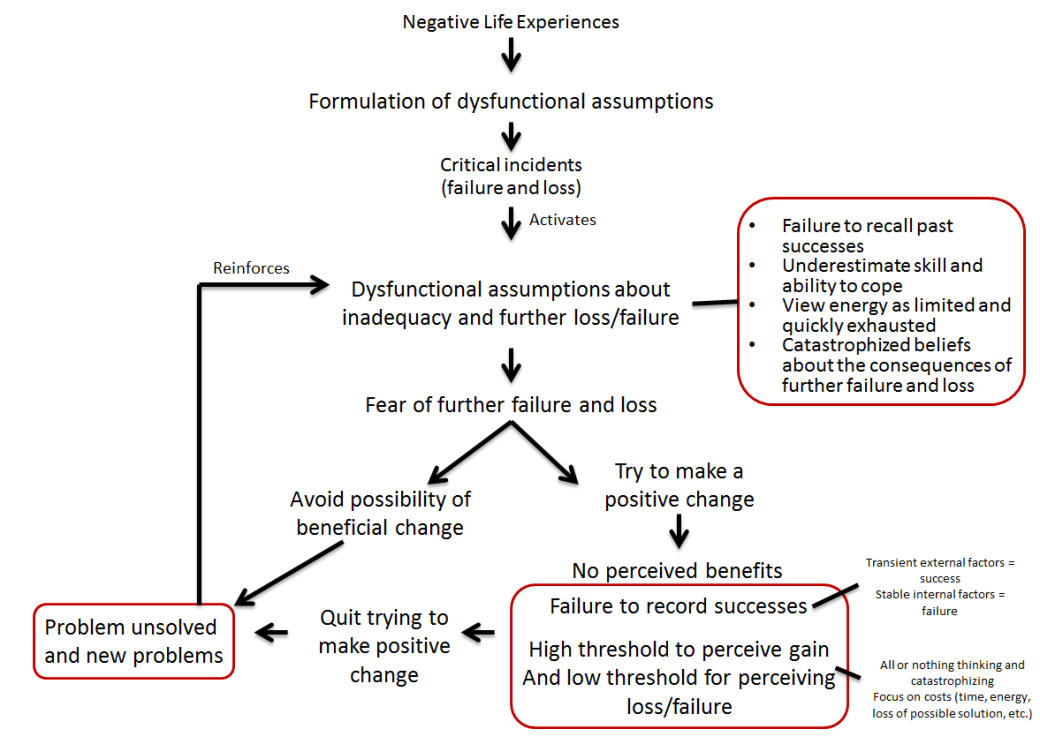

Combining the Investment Model of Resistance and the Cognitive Model of Depression

I combined Leahy’s Investment Model of Resistance with Beck’s Cognitive Model of Depression in an attempt to better understand how depression can originate and be maintained. Once we formulate dysfunctional assumptions from negative life experiences we may try to avoid critical incidents which may confirm their dysfunctional assumptions. For example, if we believe that we are unattractive we avoid asking potential mates out on dates, because the rejection could trigger too much pain and hurt. Sometimes we can be moderately successful at avoiding critical incidents and we can be “fine” for a long time. Unfortunately, loss, failure, criticism, and rejection are unavoidable parts of the human experience regardless of how much we attempt to avoid or overcompensate. When we inevitably have one of these experiences, this activates our dysfunctional assumptions. We assume our skills are inadequate, we cannot cope with further losses/failures, and our resources are minimal (viewing energy and effort as finite and minimal). We fail to recall previous successes and assume/believe our lives have been an unending and unwavering pattern of misery which influences our predictions about the effectiveness of making positive changes. We also view the costs of even minor failures/losses as catastrophic and assume we will continue to fail into the future. As Leahy explains “To the depressive, losses are not simple inconveniences. Rather, they are interpreted as salient, personally relevant, morally significant, and predictive of further losses in other domains. Ironically, because losses are so overvalued, the depressive will avoid loss at all costs.”

The Investment Model of Resistance suggests when our dysfunctional assumptions are activated, we fear further failure and loss. This fear motivates us to avoid situations that could potentially give us some benefit (go for a run, call a friend, find a new job, enhance our education, prepare healthy meals, problem solve, etc.) because each of these situations also pose the possibility of failure, loss, and rejection. In some cases the costs of making a particular change are obvious (like financial costs), in other situations the costs are more discrete. An example of a discrete cost might be the loss of energy associated with making a particular change. Some ways we may avoid making changes include requiring more “motivation” prior to making a change, trying to not think about our problems (excessive distraction and sleeping for example), demanding a 100% guarantee we will succeed before trying, and insisting someone else solve our problems for us.

If we do muster the energy and motivation to try something, we often quit at the first sign of failure or loss. Many people that are depressed try problem solving, exercising, socializing, practicing gratitude, etc. Perhaps we tried once, for a week, a month, or maybe even 6 months but our depression undermines our attempts to make progress in a number of ways.

When we are depressed we have a high threshold for perceiving gains and a low threshold for perceiving costs. When we try something and don’t get a full remission of depressive symptoms, we conclude it didn’t work at all and if something even remotely undesirable happens, we believe it to be a catastrophe. Even minor losses/failures are turned into catastrophes by the person’s own excessive and unrealistic self-blame. This is sometimes “all or nothing thinking” or “catastrophizing” and is an example of cognitively distorted thinking. Take for example, the person who musters their courage to disagree with their partner for the first time in their relationship. Naturally, when we are setting boundaries we may be changing established relationship dynamics that may be working for the other people in our relationships. So when we are assertive and our partner responds with anger and frustration because we are trying to change the relationship dynamics that may be working just fine for them, we may have the negative automatic thought “I tried and it was a disaster.” In this example, we are failing to identify our gains – practicing our assertiveness skills and communicating our boundaries. It’s similar to the person who has never played basketball concluding they will never be able to play because they missed their first three point shot. Our high threshold for perceiving gains is also influenced by our causal explanations for our successes and failures. If we do something well, we blame transient and external factors like luck or the task being so easy anyone could do it. On the other hand, when we do something poorly we blame stable and internal factors like our own inadequacy. This reaffirms our distorted beliefs that we are inadequate, all we have done is fail, and all we will ever do will fail.

When we are trying to make positive changes in our lives costs often precede benefits. So if we quit after paying the cost of making a change but before attaining the benefits, we can conclude further effort would be futile. Furthermore, the benefits may be subtle and go undetected. For example, suppose you added daily exercise to your routine. Exercising costs us time, energy, and comfort before we get the eventual, but often subtle, benefits of exercise. In this situation, it may be easy to have the negative automatic thought “exercise doesn’t help at all, I exercise daily and still feel depressed.” However, our daily exercising may be providing us with the undetected benefits of protecting us from further depression, diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, chronic pain, etc. While it may be true that we are still depressed despite exercising, we cannot know how much worse we would be without exercising. Also, if exercising does not work (provide a complete remission of depressive symptoms) we also lose it as a possible solution to our problems. As the list of possible things we can do to get out of our depression gets shorter there is additional evidence for our dysfunctional assumptions that we are inadequate and will never get better.

Our outright avoidance of making potentially beneficial changes and our trying a solution but quitting before attaining benefits, not only undermines our problem solving but it actually creates new problems. For example, if we avoid exercising, we not only have to deal with our depression persisting but we may also develop serious health complications in the future. If we try to set boundaries with a behaviorally challenging teenaged child but we quit because it didn’t get the results we wanted quick enough, the child’s behavioral problems could continue to escalate and create new problems. Similar to the patterns above, the development of new problems then reinforces the assumptions about our inadequacy and our inevitable failure.

Sadder but Wiser

Leahy also identifies another aspect depression which may contribute to resistance of making positive changes. Leahy suggests people struggling with depression develop assumptions about being “sadder but wiser” which may reinforce their dysfunctional assumptions. From their experiences of perceiving constant failures and losses, they come to believe they have an accurate view of the world as negative, hostile, and filled with suffering. They may even derive some satisfaction and a sense of superiority from arguing with others about how their view of the world is accurate, which will reinforce these assumptions. Those struggling with depression may even use their own self-sabotaged attempts to make progress as evidence in support of their arguments. This is the “I’m going to fail, I’ll try but quit when I don’t get the results I want, oh look I failed, I was right all along” rationale. As explained by Leahy “By proving that he is correct about his negativity and that the therapist is Pollyannaish in his optimism, the depressive believes that he has achieved some “victory” – he has proven the therapist wrong. Even though this may add to his sense of hopelessness, he at least feels some momentary superiority to the ‘naïve therapist.’” Granted there is no shortage of horror, despair, and suffering in the world but to focus exclusively upon these aspects of the human experience provides a biased and cognitively distorted perspective. Although you may briefly feel satisfied and superior by arguing you are “sadder but wiser”, in my opinion the costs of remaining stuck greatly outweigh these potential benefits. I was unsure about how to add the development and maintenance of this “sadder but wiser” philosophy to my model but I thought it was an interesting idea and worth mentioning in this article.

Discussion

My combining The Cognitive Model of Depression and The Investment Model of Resistance is my attempt to explain how depression is developed and maintained. As opposed to being “afraid of change” or “irrational”, my model suggests people with depression are primarily motivated to resist making positive changes in their lives because of fears of further failure and loss associated with dysfunctional assumptions. I’ve kept Beck’s emphasis on the development of dysfunctional assumptions by negative life events and the activation of these assumptions by critical incidents. I’ve attempted to expand upon the “negative automatic thoughts” portion of Beck’s model by including cognitive processes from Leahy’s Investment Model of Resistance. In my combined model, negative automatic thoughts are expanded to include fears of further failure and loss, underestimating skills and coping abilities, viewing energy as limited and easily exhausted, distorted causal explanations for successes and failures, and all or nothing thinking about progress and failure. The model I created is cyclical, explaining why the depressed individual may become “stuck” indefinitely.

An astute critic of my model may notice I did not include a path out of this cycle. While I’ll likely expand my model in the future, my goal at this time was to better understand the resistance of someone struggling with depression. However, my research suggests there are likely benefits to helping the client identify and challenge assumptions of their own inadequacy and the cost/inevitability of failure through the use of a variety of cognitive and behavioral interventions. These interventions may include cognitive restructuring techniques, activity scheduling, behavioral experiments, exposure therapy, goal setting, and problem solving training (see previous articles for more information).

Leahy’s Investment Model of Resistance is significantly more complex than the model I have created. I should also note that Leahy does not provide a visual representation of his model in Overcoming Resistance in Cognitive Therapy and I have attempted to simplify and approximate how the various factors described by his model may interact. For more information on Leahy’s model, I recommend purchasing his book. The version of Beck’s Cognitive Model of Depression was from Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Case Studies by Thomas and Drake. While I have not conducted any studies to assess the validity of my model, it is consistent with the anecdotal accounts of many people I have met who have struggled with depression, some of which provided direct, but informal feedback, about this model.

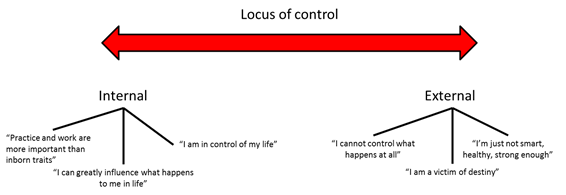

I would also like to note that by attempting to identify how the decision making of a person struggling with depression may contribute to maintaining that depression, I am not attempting to blame anyone and make them feel worse. In fact my intentions are to help expand our understanding of depression, so we can better understand and help those struggling with depression. By focusing on what we can control, and the consequences of the decisions we make, we are empowered to make positive changes in our lives.

mindfulness based theories, CBT, etc.) all have underlying philosophies about how human beings “work”, what is “healthy”, and how people can remove barriers to become more “healthy.”

mindfulness based theories, CBT, etc.) all have underlying philosophies about how human beings “work”, what is “healthy”, and how people can remove barriers to become more “healthy.”  reasons. People tend to want to minimize their choices and responsibility by suggesting they have no control over what they think or feel. There are several old videos of Albert Ellis working with clients on YouTube, and he has a very direct and almost confrontational style that I believe is reflected in the uncompromising philosophy of RET (

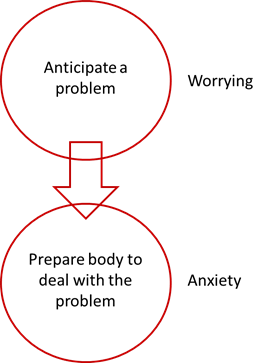

reasons. People tend to want to minimize their choices and responsibility by suggesting they have no control over what they think or feel. There are several old videos of Albert Ellis working with clients on YouTube, and he has a very direct and almost confrontational style that I believe is reflected in the uncompromising philosophy of RET ( the room with you. This is important because when you are worrying, you are thinking about “something bad” that could happen, and your brain gets confused and thinks the “something bad” is actually happening right now. So your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with the “something bad” right now, and as described above, we call these preparations “anxiety.” As advanced as our brains are, its responses to “something bad” happening can be overly simplistic. It doesn’t matter if the “something bad” is someone saying something mean to us or having to run away from a tiger in the bush, our brain and bodies tend to react in the same way (fight/run away/freeze). So the more we worry (think about what could go wrong/perceive a threat) the more your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with what could go wrong by becoming “anxious.”

the room with you. This is important because when you are worrying, you are thinking about “something bad” that could happen, and your brain gets confused and thinks the “something bad” is actually happening right now. So your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with the “something bad” right now, and as described above, we call these preparations “anxiety.” As advanced as our brains are, its responses to “something bad” happening can be overly simplistic. It doesn’t matter if the “something bad” is someone saying something mean to us or having to run away from a tiger in the bush, our brain and bodies tend to react in the same way (fight/run away/freeze). So the more we worry (think about what could go wrong/perceive a threat) the more your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with what could go wrong by becoming “anxious.” ous without worrying.

ous without worrying.

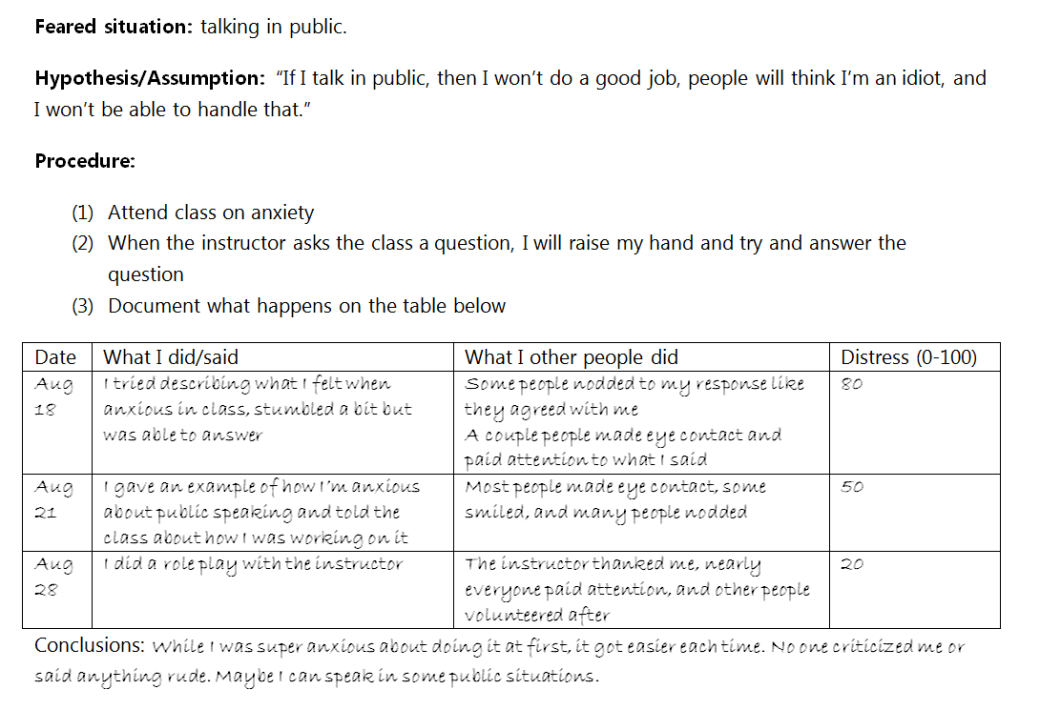

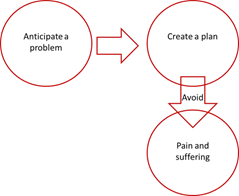

talking to authority figures, you would likely experience anticipatory anxiety before you spoke to people of authority, then when you did have to talk to someone of authority (exposing yourself to the feared situation) your anxiety would likely spike. Then when you avoid the situation by promptly leaving, your anxiety will naturally go down. Unfortunately, when we cope with anxiety by avoiding challenging situations we cannot challenge our assumptions that the situation is dangerous, we cannot challenge our assumptions that we cannot handle the stressful situation, nor can we learn how to handle the situation more effectively. So then the next time we exposure ourselves to the stressful situation we experience a similar amount of anxiety.

talking to authority figures, you would likely experience anticipatory anxiety before you spoke to people of authority, then when you did have to talk to someone of authority (exposing yourself to the feared situation) your anxiety would likely spike. Then when you avoid the situation by promptly leaving, your anxiety will naturally go down. Unfortunately, when we cope with anxiety by avoiding challenging situations we cannot challenge our assumptions that the situation is dangerous, we cannot challenge our assumptions that we cannot handle the stressful situation, nor can we learn how to handle the situation more effectively. So then the next time we exposure ourselves to the stressful situation we experience a similar amount of anxiety.

ions throughout my day. What does practicing mindfulness look like? Take a breath, notice the air filling your lungs, notice your rib cage expanding, notice your heart beat, just notice how it feels. Focus on those things, and without judgment (“It should be deeper”, “it should be slower”, “it should be…”), just notice the way it is. Congratulations, you have just practiced mindfulness. It’s that simple.

ions throughout my day. What does practicing mindfulness look like? Take a breath, notice the air filling your lungs, notice your rib cage expanding, notice your heart beat, just notice how it feels. Focus on those things, and without judgment (“It should be deeper”, “it should be slower”, “it should be…”), just notice the way it is. Congratulations, you have just practiced mindfulness. It’s that simple.