Although this will likely reduce the number of “likes” I get for this post, I believe it is important to begin with some honesty. Overcoming anxiety is hard work. Most people want a simple and easy answer that can make all of their suffering go away. However, for every complicated and messy problem there are many simple and easy answers that are ineffective. For example, in Canada the use of antidepressants increased over 450% between 1981 and 2000, but the demand for mental health services has never been higher. This post is not an “8 easy steps to being less anxious” kind of post, it is more of a “if you work really hard, stay determined despite set-backs, and keep an open-mind about trying new things you may be able to make some real improvements to your life” kind of post.

Anxiety and Avoidance

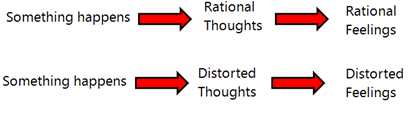

Anxiety is a normal reaction to perceived threats. However, when we have a tendency to focus on threatening situations, the problems in our lives, we are fueling excessive amount of anxiety. One way we attempt to reduce the amount of anxiety we experience is by avoiding challenging situations. However, avoidance prevents us from overcoming our fears. Furthermore, as we avoid more and more things, our lives become more and more restricted.

For example, if you had social anxiety and were terrified of  talking to authority figures, you would likely experience anticipatory anxiety before you spoke to people of authority, then when you did have to talk to someone of authority (exposing yourself to the feared situation) your anxiety would likely spike. Then when you avoid the situation by promptly leaving, your anxiety will naturally go down. Unfortunately, when we cope with anxiety by avoiding challenging situations we cannot challenge our assumptions that the situation is dangerous, we cannot challenge our assumptions that we cannot handle the stressful situation, nor can we learn how to handle the situation more effectively. So then the next time we exposure ourselves to the stressful situation we experience a similar amount of anxiety.

talking to authority figures, you would likely experience anticipatory anxiety before you spoke to people of authority, then when you did have to talk to someone of authority (exposing yourself to the feared situation) your anxiety would likely spike. Then when you avoid the situation by promptly leaving, your anxiety will naturally go down. Unfortunately, when we cope with anxiety by avoiding challenging situations we cannot challenge our assumptions that the situation is dangerous, we cannot challenge our assumptions that we cannot handle the stressful situation, nor can we learn how to handle the situation more effectively. So then the next time we exposure ourselves to the stressful situation we experience a similar amount of anxiety.

Overcoming anxiety can be accomplished a number of ways. However, research strongly suggests that one of the most effective strategies for overcoming anxiety is something called “exposure therapy.” Exposure therapy rests on the premise that if we can expose ourselves to our anxiety provoking situations in a certain way, we can learn: the situation isn’t as dangerous as we assume, we can handle the challenging situation, and we can practice skills to better handle similar situations in the future.

Exposure therapy

- Begin by creating a list of situations you avoid

- Rate how much anxiety you suspect you will experience in each of these situations on a scale from 0-100

- Select a situation that will provoke a small amount of anxiety – set yourself up for success

- Create a plan to expose yourself to this situation –when? Where?

- Expose yourself to the situation

- When you are in the situation try and pay attention to what is going on around you as opposed to what is happening in your body or distracting yourself (looking at your phone, talking to a friend, reading a book, etc.)

- Stay in the situation until your anxiety has diminished, do not just leave when you feel some anxiety

- After your anxiety has gone down, ask yourself what you have learned about how dangerous the situation was, what you have learned about your ability to cope (did you survive?), and some skills you could practice to handle the situation more competently in the future

- If you notice yourself going over and over the situation in your mind, distract yourself by doing something engaging

- When you are able, expose yourself to the same situation again and again until you do not feel very much anxiety at all in that situation

- Once you have completed the first anxiety provoking situation, move on to another situation on your list of anxiety provoking situations and repeat this process

By exposing ourselves to anxiety provoking situations appropriately, we are able to reduce the amount of anxiety experienced when we face similar situations in the future.

Some notes about exposure therapy:

Exposure therapy can be immensely effective for anxiety created by many different situations. Personally, I have seen clients make radical changes in only a small number of sessions when they are committed to their exposure plan. However, it is important to remember than some situations are actually dangerous and we are not always exaggerating the danger in our minds. Therefore, I do not encourage people to behave recklessly, for example standing in a busy highway, going down dark alleys at night, or committing any crimes. Also, this article only describes one type of exposure therapy, something called “in vivo” exposure therapy and this type of exposure therapy cannot be used to overcome some anxiety provoking situations. Obviously, we cannot expose ourselves to our fear of our own death (at least not more than once), to fears of loved ones dying, or to fears of natural disasters. For these types of hypothetical fears, we may need to practice something called “imaginal exposure” which is not described in this article.

Some notes for therapists:

Many clients struggle with creating the motivation to engage with exposure therapy. When we are distressed we often resort to coping mechanisms that are familiar to us, even if they are not helpful. It can be useful to go slow with clients and discuss the costs and benefits of avoidance. Encourage the client to consider what their life may be like if they continue to avoid anxiety provoking situations indefinitely and/or consider the opportunities their avoidance may have already cost them. Remember, it is not our job to convince the client to do anything. Instead we are there to help them make informed decisions. If the client chooses to continue to avoid, while knowing the consequences of this decision, that is their choice and that should be respected.

Processing what the client has learned from exposing themselves is just as important as collaborating with the client to design the exposure activity. “what did you learn from exposing yourself to this situation?”, “what did you learn about your ability to cope with the situation?”, “what did you learn about your anxiety in general?” “what did you learn about your fears?” – Questions like these can be very helpful.