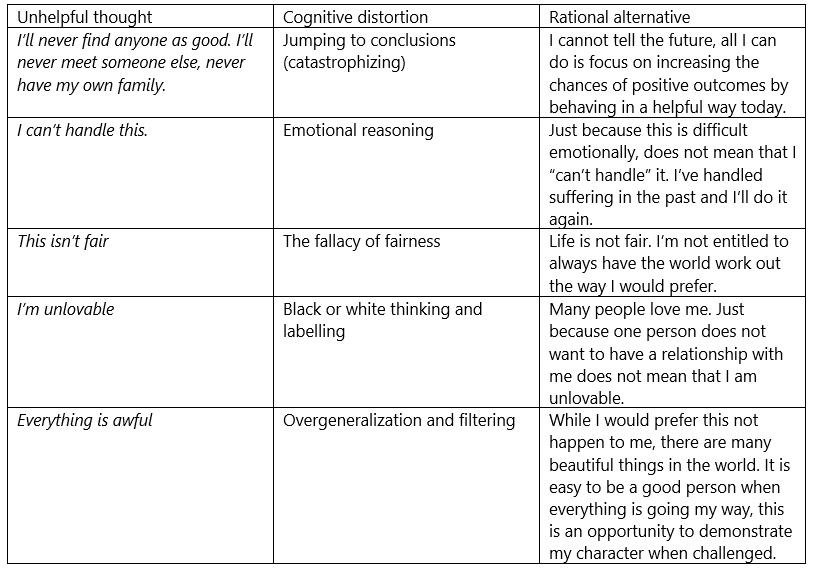

I’ll never find anyone as good. I’ll never meet someone else, never have my own family. I can’t handle this. This isn’t fair. I’m unlovable. Everything is awful.

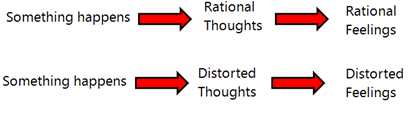

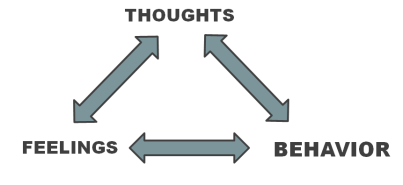

Most people are familiar with thoughts like these. When under intense stress, like the loss of a significant relationship, our minds often go to those dark places. Sometimes our thoughts are irrational and since these thoughts are extreme, the emotions they evoke are also irrational. I tell clients all the time that I do not want them to be an unfeeling robot. If we suffer a significant loss we should feel some grief, if we are treated unfairly it is normal to feel angry, and it is okay to be sad sometimes. However, sometimes we have emotional reactions which are disproportionate to the situation. It is these intense emotional reactions which usually lead to behavior that is inconsistent with our values and goals. Since we know emotions are caused by thinking, we can reduce the intensity of irrational emotional responses by changing the irrational thinking evoking them.

“There are no facts, only interpretations.”

Dr. Aaron Beck is widely considered the father of Cognitive Therapy. He was trained in the classical forms of therapy pioneered by Sigmund Freud (Psychodynamic Therapy). Psychodynamic Theory suggests that our thoughts are the product of unconscious or subconscious forces within our psyche. In other words, this theory suggests that our thoughts mean something about us. While at a dinner party, Dr. Beck met a woman and this interaction would change psychotherapy forever. The story is that this woman explained she was depressed and she believed that no one loved her/she was unlovable. Instead of going down the usual therapeutic road, Dr. Beck decided to try something different. He asked her to evaluate the evidence for her beliefs. To her surprise, the woman was able to recognize that there were several people in her life that loved her and when she focused on this, her sadness dissipated (listen to this great podcast for more information). While working with severely depressed patients in his clinic, he noticed several common thinking errors within the thoughts of his patients. Today these thinking errors are called “cognitive distortions.” By identifying and challenging cognitive distortions, our thinking can become more rational and as a result our emotions will also become more rational.

In the following table I demonstrate how the “three column technique” can be used to challenge cognitively distorted thoughts. In this exercise you identify your distressing thoughts, identify cognitive distortions taking place, and try and come up with more rational thoughts.

While a full description of all of the common cognitive distortions is beyond the scope of a single blog post, I will post a worksheet I use with clients on the self-help resources page that goes over them in greater detail.

When I work with clients, I typically go over a list of some common cognitive distortions. The vast majority of clients are able to recognize that they have many thoughts consistent with these unhelpful thinking styles. Clients struggling with depression usually filter out all of the good things in life, those struggling with anxiety are often plagued with catastrophizing, and people overwhelmed with anger desperately want the world to work the way they want (should/musts and the fallacy of fairness). We all think cognitively distorted thoughts sometimes, it is normal. The refreshing thing about thinking habits is that they can be changed. The first step to changing our thinking is building our awareness of our thoughts. Simply reading this post and the list of common cognitive distortions on the self-help page can help you with becoming more aware of your unhelpful thinking patterns.

Personally, learning about cognitive distortions has changed my life. Challenging my unhelpful thoughts insulates me from distress that comes with being a human being. When I am irrationally frustrated about something (like a hockey game) I pull out my journal and practice these skills. When I go through a more significant challenge (bereavement, financial concerns, trauma, etc.) I use the same skills. Before learning these theories and techniques, I would stay up for hours on end, just laying in bed ruminating about things. Now I am able to process what is going on for me and let it go. Hopefully with some practice, you will be able to do the same.

The question of “how do we lead a healthy life” has been explored by humans for a very long time. Researchers at SFU have been attempting to modernize the very old idea of the “Wellness Wheel.” This model breaks down the concept of wellness into seven primary dimensions Simply put, we can improve our wellness by attempting to maintain balance among these dimensions. I suspect most people can anticipate how their well-being would suffer if they were to over focus on one dimension at the cost of the others.

The question of “how do we lead a healthy life” has been explored by humans for a very long time. Researchers at SFU have been attempting to modernize the very old idea of the “Wellness Wheel.” This model breaks down the concept of wellness into seven primary dimensions Simply put, we can improve our wellness by attempting to maintain balance among these dimensions. I suspect most people can anticipate how their well-being would suffer if they were to over focus on one dimension at the cost of the others. better than the behavior habits of depressed people. When you ask a person with depression about their daily routines, it is not unusual in my experience for them to describe a daily routine dominated by social withdrawal, minimal exercise, low goal-oriented behavior, unhealthy eating habits, and irregular sleeping patterns. Paradoxically, depression often reduces self-care which in turn feeds depression. I’ve often believed that if we were to take a mentally “healthy” person and force them to behave the same way as a depressed person, it would only be a matter of time before the despair, sadness, and loneliness set in. Regardless of what came first, research suggests we can reduce feelings of depression by improving self-care.

better than the behavior habits of depressed people. When you ask a person with depression about their daily routines, it is not unusual in my experience for them to describe a daily routine dominated by social withdrawal, minimal exercise, low goal-oriented behavior, unhealthy eating habits, and irregular sleeping patterns. Paradoxically, depression often reduces self-care which in turn feeds depression. I’ve often believed that if we were to take a mentally “healthy” person and force them to behave the same way as a depressed person, it would only be a matter of time before the despair, sadness, and loneliness set in. Regardless of what came first, research suggests we can reduce feelings of depression by improving self-care.