What is anxiety?

Anxiety is a normal reaction to perceiving a threat. When we believe something important to us (our lives, our jobs, our families, etc.) is threatened, our bodies prepare us to deal with this threat. Our muscles tense, our heart beats faster, our breathing may get rapid and shallow, etc. these are the physical symptoms of anxiety.

How does worrying influence anxiety?

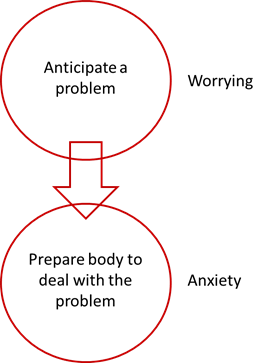

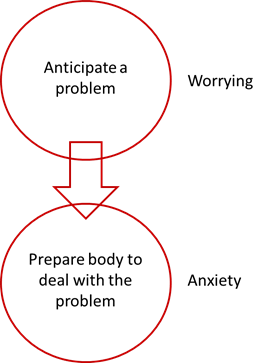

There is a lot of research suggesting people who struggle with excessive anxiety have difficulties tolerating uncertainty. In other words they struggle with not knowing what might happen. “Worrying” is attempting to anticipate threats that may occur in the future – trying to figure out what might happen. People tend to believe that if they can just predict everything that could go wrong, they can plan and problem solve, and then they will be safe. However, our brains easily confuse real threats with imagine threats. For example, if you were extremely afraid of spiders, seeing photos of spiders, seeing videos of spiders, or just thinking about spiders might be enough to trigger anxiety – even if you know the spider in the photo is not actually in the room with you. This is important because when you are worrying, you are thinking about “something bad” that could happen, and your brain gets confused and thinks the “something bad” is actually happening right now. So your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with the “something bad” right now, and as described above, we call these preparations “anxiety.” As advanced as our brains are, its responses to “something bad” happening can be overly simplistic. It doesn’t matter if the “something bad” is someone saying something mean to us or having to run away from a tiger in the bush, our brain and bodies tend to react in the same way (fight/run away/freeze). So the more we worry (think about what could go wrong/perceive a threat) the more your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with what could go wrong by becoming “anxious.”

the room with you. This is important because when you are worrying, you are thinking about “something bad” that could happen, and your brain gets confused and thinks the “something bad” is actually happening right now. So your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with the “something bad” right now, and as described above, we call these preparations “anxiety.” As advanced as our brains are, its responses to “something bad” happening can be overly simplistic. It doesn’t matter if the “something bad” is someone saying something mean to us or having to run away from a tiger in the bush, our brain and bodies tend to react in the same way (fight/run away/freeze). So the more we worry (think about what could go wrong/perceive a threat) the more your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with what could go wrong by becoming “anxious.”

Why do I worry so much?

Researchers Dugas and Robichaud identify five beliefs that keep people stuck in a cycle of excessive worrying. If we believe these things, we are encouraged to worry as much as possible. These beliefs are:

1) “Worrying helps find solutions to problems.” While recognizing the problem is one part of problem solving, it is no longer helpful when we start worrying about problems with a low probability of occurring. For example, if you are going camping it makes sense to recognize that it could rain (anticipate a problem with a reasonable probability of occurring) and plan accordingly by bringing a tarp. However, it is less helpful to plan for a satellite falling from orbit and landing on your campsite. This sounds ridiculous but we often do we worry about all the things that could go wrong as opposed to what is likely to happen.

2) “Worrying helps motivate me to get things done.” Similar to the previous rationalization for worrying, perhaps some worrying does help motivate you. It makes sense to remember you have a test coming up in a couple of weeks, so you can start studying for the test. However, when we excessively worry we can often get overwhelmed by anxiety. If we are worrying about our test in a couple of weeks, about the bus maybe being late, about our partners not actually loving us, about what we are going to get our mother for her birthday, about the assignment due next month, etc. we may experience too much anxiety and being distracting ourselves, procrastinating, using substances to calm down, or use another unhelpful coping mechanism.

3) ‘Worrying prepares me for uncomfortable emotions.” This belief reflects the idea that if we worry about something bad happening, we will be less disappointed, sad, or guilty should that bad thing happen. Unfortunately, this belief will keep us locked in an endless pattern of worrying “just in case.”

4) “Worrying can prevent bad things from happening.” Some people believe that if they just worry enough, “magical thinking” will prevent what we are worried about from happening. If this were true, then we would become stuck in an endless cycle of worrying about all the bad things that could happen.

5) “Worrying is a positive part of my personality.” This is when we believe that worrying shows we are caring, loving, or conscientious. However, worrying too much can actually annoy and frustrate the people in your life, and push them away. Furthermore, there are many ways we can be caring, loving, and conscienti ous without worrying.

ous without worrying.

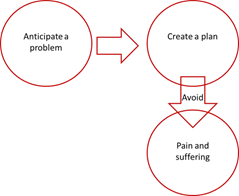

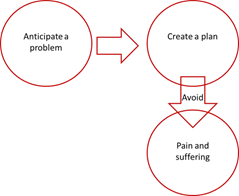

A major theme within these beliefs is the idea that worrying will somehow prevent or reduce our pain and suffering. In other words, people think that if they can just anticipate all the problems, they can create some kind of plan, which “fixes” the “problem”, which will protect us from the pain and suffering we would experience if the problem were to occur. For example, if I worry about my kid using drugs, I can create a plan to talk to them about drug use, so I can avoid the pain and suffering I would experience if my kid were to use drugs.

However, when we anticipate problems, our mind tells our body to prepare to deal with problems, it tells our body to become anxious. Most people find anxiety painful and describe it as suffering. So ironically, by anticipating problems, to avoid pain and suffering, we are actually creating our own pain and suffering.

Many people want to spend a lot of time anticipating the bad things that could happen in their lives (worrying) but don’t want the anxiety. However, our brains are not wired for this and by choosing to worry, we are indirectly choosing to have anxiety.

When is it helpful to worry?

Worrying can be helpful in some situations but we want to limit our worrying because excessive worrying will lead to excessive anxiety. For example, it can be helpful to anticipate and prepare for:

a) Things with a reasonable probability of happening,

b) Things we can reasonably do something about now or in the immediate future,

c) Things that would pose a legitimate threat to our health, safety, or goals.

If a situation meets all three of these criteria, it might be worth your worrying. For example, people often worry about public speaking. If we know we have to give a presentation in class, there is a reasonable probability we will have to speak in public. Perhaps a large portion of your grade is dependent on how you do in your presentation, so it may be important to you to do well, in which case it would be prudent to prepare thoroughly. By anticipating this challenge, we can prepare by doing our research and practicing our presentation thoroughly. If we are thinking about the challenges we may face while giving our presentation during a study session scheduled to work on your presentation, this would be helpful. However, worrying about giving your presentation is no longer helpful when you are lying in bed at 3 am wanting to sleep, because these is nothing you could reasonably do at that time and focusing on the presentation is interfering with your other important life goals (like getting a good night’s sleep). Worrying about being laughed out of the classroom and losing all your friends because you did poorly on a presentation isn’t helpful because, in my opinion, it doesn’t have a reasonable probability of occurring. It is also important to put the consequences of giving an imperfect presentation into perspective. While you might not get the grade you want, you will likely be physically fine – no one will chop your hand off for doing poorly.

How do I experience less anxiety?

This is a very old and complicated question with several different answers. For moderate to severe levels of anxiety medication can help, but medications can have side effects. Taking medication can also be relatively easy, you simply take some pills throughout your day. Other ways to reduce anxiety typically take more work, but they also have some benefits medication does not. In therapy, I usually start by recommending daily exercise, getting 8-9 hours of sleep per night, and eating a balanced diet. While people may not see the connection between these habits and their anxiety, research strongly suggests each of these interventions. These habits also come with a wide array of other benefits as well. Healthy living habits serve as the foundation upon which we can build wellness.

Then there are a number of mental exercises people can practice to reduce worrying and anxiety. One of which is called mindfulness which can be described as practicing non-judgmental awareness and acceptance of the present moment. This is when you pay attention to what is happening right now, in the room where you are, in your body, and in your mind. Then we accept the thoughts, feelings, sensations, and images in the present moment without judgement. So maybe you check-in with your body and notice some sadness, and instead of trying to get rid of the sadness because it is “bad” you accept the sadness without judging it as either good or bad. This can help reduce anxiety because when we are paying attention to the present moment, we cannot be attempting to anticipate the “bad things” that could happen in the future. As we continue to practice directing our attention to the present, this gets easier and we actually change the way our brains work.

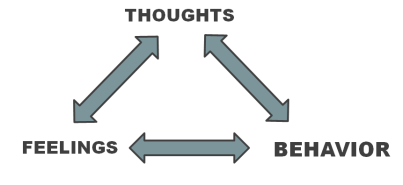

The cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) approach to reducing anxiety includes changing patterns of thinking and behaving which maintain anxiety. We question the beliefs that maintain our worrying, our unhelpful ways of dealing with problems, the beliefs about our vulnerability to “bad things happening”, and our ability to cope with challenges. We largely do this through a series of activities designed to challenge unhelpful beliefs. For example, a person anxious about being in a public place will create a series of exposure exercises in which they expose themselves to their feared situations so they learn that their fear is irrational and that they can cope with being in public places. CBT is direct, short-term, and it can take a willingness to take some “risks.” There is a lot of research supporting CBT as a front-line treatment for anxiety. In my experience, CBT is most effective when the feared situation is concrete and specific. CBT can be offered in individual therapy, group therapy, self-help books, and online.

I’ve tried everything before and it hasn’t worked, now what do I do?

This question is an overgeneralization – there is no way anyone could try “everything.” Instead, it is likely that you have tried several or many things in the past and have not gotten the desired results. However, there are many different medications, many different activities that promote wellness (yoga, joining a sports team, trying a new hobby, finding a new job, journaling, etc.), and many different kinds of therapy. Even among cognitive-behavioral therapists there is a lot of variation in how therapists actually practice. If we are trying to find a reason to give up (“I’ve tried everything”), this might mean we don’t actually want to put the work in to make changes, and that is okay. There may be a time in your life when you are more ready, willing, and able to try something new. If that time comes, hopefully this article has given you some ideas you could try.

mindfulness based theories, CBT, etc.) all have underlying philosophies about how human beings “work”, what is “healthy”, and how people can remove barriers to become more “healthy.” People might be surprised to know there are a number of different variations of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). One type of CBT is called Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET) and it was created by Albert Ellis. This article describes the underlying philosophies of RET and has been adapted from Bill Borcherdt’s book “Think Straight! Feel Great! 21 guides to Emotional Self-Control.”

mindfulness based theories, CBT, etc.) all have underlying philosophies about how human beings “work”, what is “healthy”, and how people can remove barriers to become more “healthy.” People might be surprised to know there are a number of different variations of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). One type of CBT is called Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET) and it was created by Albert Ellis. This article describes the underlying philosophies of RET and has been adapted from Bill Borcherdt’s book “Think Straight! Feel Great! 21 guides to Emotional Self-Control.” reasons. People tend to want to minimize their choices and responsibility by suggesting they have no control over what they think or feel. There are several old videos of Albert Ellis working with clients on YouTube, and he has a very direct and almost confrontational style that I believe is reflected in the uncompromising philosophy of RET (click here for a classical example of RET at work). I’m not saying the advice listed above is bad advice, just that I suspect giving this advice in a way that clients could receive it non-defensively could take some tact.

reasons. People tend to want to minimize their choices and responsibility by suggesting they have no control over what they think or feel. There are several old videos of Albert Ellis working with clients on YouTube, and he has a very direct and almost confrontational style that I believe is reflected in the uncompromising philosophy of RET (click here for a classical example of RET at work). I’m not saying the advice listed above is bad advice, just that I suspect giving this advice in a way that clients could receive it non-defensively could take some tact.  the room with you. This is important because when you are worrying, you are thinking about “something bad” that could happen, and your brain gets confused and thinks the “something bad” is actually happening right now. So your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with the “something bad” right now, and as described above, we call these preparations “anxiety.” As advanced as our brains are, its responses to “something bad” happening can be overly simplistic. It doesn’t matter if the “something bad” is someone saying something mean to us or having to run away from a tiger in the bush, our brain and bodies tend to react in the same way (fight/run away/freeze). So the more we worry (think about what could go wrong/perceive a threat) the more your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with what could go wrong by becoming “anxious.”

the room with you. This is important because when you are worrying, you are thinking about “something bad” that could happen, and your brain gets confused and thinks the “something bad” is actually happening right now. So your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with the “something bad” right now, and as described above, we call these preparations “anxiety.” As advanced as our brains are, its responses to “something bad” happening can be overly simplistic. It doesn’t matter if the “something bad” is someone saying something mean to us or having to run away from a tiger in the bush, our brain and bodies tend to react in the same way (fight/run away/freeze). So the more we worry (think about what could go wrong/perceive a threat) the more your brain tells your body to get ready to deal with what could go wrong by becoming “anxious.” ous without worrying.

ous without worrying.

The question of “how do we lead a healthy life” has been explored by humans for a very long time. Researchers at SFU have been attempting to modernize the very old idea of the “Wellness Wheel.” This model breaks down the concept of wellness into seven primary dimensions Simply put, we can improve our wellness by attempting to maintain balance among these dimensions. I suspect most people can anticipate how their well-being would suffer if they were to over focus on one dimension at the cost of the others.

The question of “how do we lead a healthy life” has been explored by humans for a very long time. Researchers at SFU have been attempting to modernize the very old idea of the “Wellness Wheel.” This model breaks down the concept of wellness into seven primary dimensions Simply put, we can improve our wellness by attempting to maintain balance among these dimensions. I suspect most people can anticipate how their well-being would suffer if they were to over focus on one dimension at the cost of the others. better than the behavior habits of depressed people. When you ask a person with depression about their daily routines, it is not unusual in my experience for them to describe a daily routine dominated by social withdrawal, minimal exercise, low goal-oriented behavior, unhealthy eating habits, and irregular sleeping patterns. Paradoxically, depression often reduces self-care which in turn feeds depression. I’ve often believed that if we were to take a mentally “healthy” person and force them to behave the same way as a depressed person, it would only be a matter of time before the despair, sadness, and loneliness set in. Regardless of what came first, research suggests we can reduce feelings of depression by improving self-care.

better than the behavior habits of depressed people. When you ask a person with depression about their daily routines, it is not unusual in my experience for them to describe a daily routine dominated by social withdrawal, minimal exercise, low goal-oriented behavior, unhealthy eating habits, and irregular sleeping patterns. Paradoxically, depression often reduces self-care which in turn feeds depression. I’ve often believed that if we were to take a mentally “healthy” person and force them to behave the same way as a depressed person, it would only be a matter of time before the despair, sadness, and loneliness set in. Regardless of what came first, research suggests we can reduce feelings of depression by improving self-care.